More than Words

The speech-language pathology field has historically been dominated by White women. Now, Emerson is diversifying the field, putting in place measures to make the profession more inclusive. Here’s why it matters.

By David Ertischek

Photo illustration by Will Kastrinakis

Valerie Johnson recalls how disconnected she sometimes felt when she was a practicing speech-language pathologist.

“I was a clinician for many years and oftentimes I found myself as the only clinician of color in the school district. It was very isolating,” said Johnson (below right), now a distinguished scholar-in-residence in Emerson’s Communication Sciences and Disorders (CSD) Department.

To say there is a lack of diversity in the speech-language pathology field is an understatement.

In 2021, only 8 percent of American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) members identified as a racially minoritized group. In contrast, 38 percent of the US population identified as a racially minoritized group in that same year.

As the country continues to reckon with systemic racism, the communication sciences and disorders field is evolving, with Emerson leading the way: The College’s CSD Department is creating opportunities to improve the demographic inequities within the profession. It’s a profession that is increasingly in demand: speech-language pathologist now ranks #10 on the U.S. News & World Report’s list of “100 Best Jobs” and #3 within healthcare jobs.

“Bringing more cultural and linguistic diversity into our field is a pressing issue. Very few speech pathologists are bilingual,” said Ruth Grossman, professor and CSD chair. “People need services to support their communication in a language they are comfortable in. It’s problematic if we cannot provide that and need to work via interpreters. This is an urgent need in our field.”

Taking Action

The CSD Department recently created a concrete, holistic action plan to effect change, at the very least at Emerson. One piece of that plan involves increasing diversity among faculty.

“That’s a direct result of having created a very purposeful and intentional new job posting and recruiting plan,” said Grossman (photo left). “And we’re still working on expanding that process to staff hires as well.”

Two recently hired faculty of color will transition to leadership positions starting in the fall semester. Distinguished Scholar-in-Residence Nydia Bou, who was born and raised in Puerto Rico, will take over as chair from Grossman. And Valerie Johnson, who identifies as African American, will be leading the online master’s program Speech@Emerson.

On campus, the department’s student cohort has increased BIPOC representation for several years in a row. In 2020, 17 percent of its population identified as BIPOC; it jumped to 36 percent in 2021, and stayed steady around that percentage this year, Grossman said, adding that many students mentioned being attracted to the program due to the department’s statement on racial equity, found on its website.

Separately, in 2020, CSD graduate students recognized that curriculum resources did not train them fully for the diverse client population they will serve throughout their careers. Proactively working with the faculty and CSD leadership, the students created a robust, culturally inclusive and anti-racist resource document that was quickly adopted and infused into curricula.

Astrid Esquilín Nieves, MS ’21, who co-led the effort, spoke about the inadequacies of relying on “proper English” in academia and standardized tests, which are used to diagnose learning disabilities or hearing deficiencies, among others.

“The difference is that you can speak African-American English at home, but not in writing. In our field, we will speak the dialects,” Nieves (photo left) said in a 2020 Emerson Today article. “We have to provide standardized assessment and ask: How do we take into account dialectal differences? And how will it impact testing? How will it be different than the expected [proper American English] answer? It’s important to consider different dialects of kids.”

Pathways to Speech-Language Pathology

Speech@Emerson, the online-only master’s degree program that launched in 2019 and mirrors Emerson’s on-campus graduate program, is also working to diversify the field. By making the discipline more accessible to students across the country, it increases the knowledge of these programs in communities that might not have previously been familiar with them. The online program’s enrollment is close to 1,200 students, almost half of whom identify as BIPOC, and who hail from 44 states.

“One of the main reasons we wanted to have an online program was to have a broader reach and provide people in underserved areas with well-trained speech pathologists.” —Ruth Grossman

Speech@Emerson students also complete their clinical placements in locations across the country, including many in areas that have traditionally had limited access to speech-language pathologists.

“One of the main reasons we wanted to have an online program was to have a broader reach and provide people in underserved areas with well-trained speech pathologists,” said Grossman.

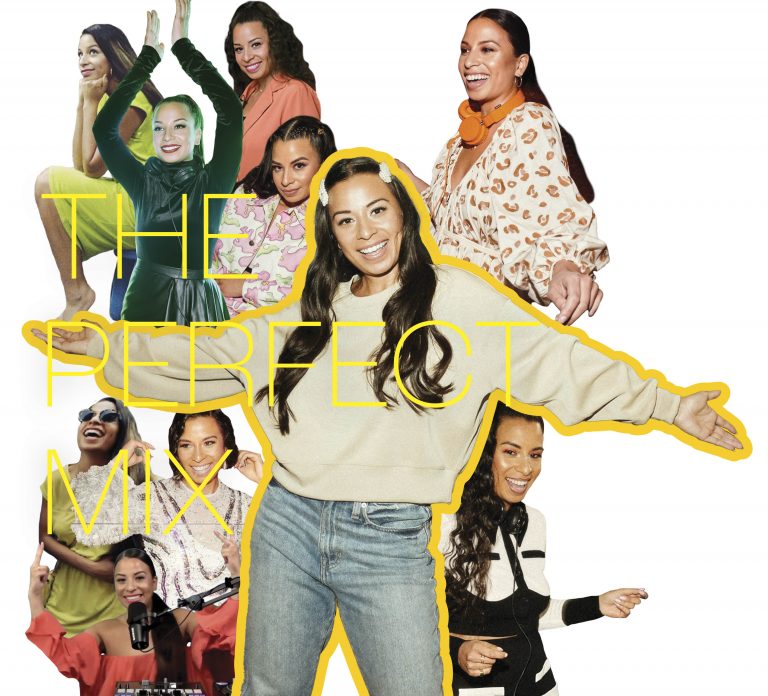

Speech@Emerson student Yaneiri Hernandez Ochoa, MS ’23, said seeing a person of color as a facilitator in her class was motivating.

“It was important for me to see her. I bet she’s had to deal with some of the same things I have as a Brown woman,” said Ochoa (photo right), who lives in southern California. “I felt peace. I felt happy and included. I felt like she understood me.”

Ochoa said she valued class discussions about how to work with clients no matter their cultural, racial, socioeconomic, or language backgrounds, as well as the importance of how those differences might subconsciously impact a clinician’s intervention or assessment work.

Like Ochoa, Valerie Johnson underscored the importance of being among other BIPOC colleagues. As an example, she said she specifically sought out a doctoral program with more BIPOC representation—which was unlike her undergrad and graduate experiences—and said she appreciated being part of a community and feeling a sense of belonging.

“I didn’t have that at the grad level. I wasn’t invited to study sessions,” she said.

When BIPOC students see themselves reflected among professional speech-language pathologists, it increases the viability of the profession for them and opens doors as a career option within their community.

“If it weren’t for me being curious as an aide in the classroom and asking a speech pathologist what their profession was, I wouldn’t have known that speech therapy is a profession,” said Ochoa. “I don’t think I’d ever heard of a speech pathologist [before that].”

Another diverse pathway to the speech-language pathology field that Emerson has opened involves a new partnership with Roxbury Community College (RCC), just a few miles down Tremont Street. As part of this new relationship, RCC students who have completed the Health Professions two-year undergraduate program can easily transfer into Emerson’s CSD major. According to Grossman, RCC students typically know about nursing but are not always aware of speech-language pathology as a potential career path. RCC staff and faculty have begun to familiarize students with the profession as a way to help people with speech, language, hearing, swallowing, and other communication abilities.

Cultural Awareness at the Robbins Center

The College’s Robbins Center, the primary clinical training facility associated with Emerson’s CSD program, serves clients who represent cultures from across the globe. The diversity of its clientele supports the Center’s core mission of cultural humility in family-centered practice, said Lynn Conners, MSSp ’97, director of clinical programs at the Center.

“Identifying where there’s systemic racism within our practices is work that we’re thinking about on a daily basis,” said Conners. “What are the assessment tools to use? What is the research we’re using? And is it inclusive of the clients we’re serving?”

In practicum planning meetings, Conners and her colleagues regularly discuss the importance of understanding cultural variables. She said the speech-language pathology field as a whole is talking more about social justice and taking into account demographics such as gender identity and neurodiversity, and the intersectionality with other communication disorders. Considering those factors in decision making around intervention and intervention planning has also increased, and is more routine than it was even three to five years ago, Conners said.

The COVID pandemic only heightened the need for this awareness.

Conners said that during the past two years, clients had less access to services, creating even greater inequity. She said the pandemic also added more of a burden to speech-language pathologists’ work, as they dealt with moving to online platforms, diagnosing clients virtually, and other stressors that many in the healthcare field have faced.

“Identifying where there’s systemic racism within our practices is work that we’re thinking about on a daily basis.” —Lynn Conners

But a silver lining is that virtual sessions turned out to be effective for certain patients, which is why the Robbins Center is continuing to offer both in-person and virtual appointments through the end of 2022. Virtual sessions can increase accessibility by reducing transportation issues and give a clinician a valuable view into the client’s homelife. Conners hopes that the Council on Academic Accreditation will continue to support the hybrid modality, allowing the Robbins Center to offer hybrid services.

“In the early days of the pandemic, there were many children who needed services who weren’t able to access them. As we’ve become savvier and more skilled providers of telehealth, we can make better distinctions about particular clients and who really needs in-person services,” she said. “We’ve also learned that there are some children, and maybe even younger than you’d expect, upper elementary schoolchildren, who actually do quite well in the telehealth modality to continue to work on their language and speech communication needs.”

Being virtual has also provided a window into clients’ homes, allowing clinicians to see what toys or materials are readily available to help engage the child in a session, and making the clinicians aware of any barriers that might exist at home.

While the pandemic has altered how the Robbins Center provides services, Conners also said she is excited for the future of the speech-language pathology field: “I’m anxious for our [recent graduates] to be three to five years into their careers so I can start hiring them.”