Transforming Narratives of Gun Violence

By Eric Gordon

The media narratives surrounding the tragedies in Uvalde, Buffalo, and Highland Park have focused on answering the unanswerable: Why would someone do this? And what actually happened at the scene? Political figures rehearse their tired performances of indignation and send their thoughts and prayers. Republicans, and their friends at the NRA, advocate for arming teachers and fortifying schools. Democrats ask for “common-sense” gun regulations. The public outcry from all sides of the political debate rages for a few weeks. We focus on the tragedy experienced by the victims’ families, gesture toward memorializing their memories, and then the steady cycle of the news moves on.

We have a gun problem in the United States, one that is exacerbated by the stories we tell about it. If anything is ever going to change, we need to become far more deliberate about how we tell stories of the impact and causes of our gun problem. For too many Americans, gun violence plays out like a serial soap opera: tragedy happens, we mourn, and we move on. In under-resourced urban communities that are burdened by the realities and consequences of systemic racism, gun violence is the everyday story—one that, despite media inattention to the tragedy of “gang-related” or “Black on Black” shootings, never goes away with the media cycle. In 2021, there were 20,726 gun-related deaths in the United States, excluding suicide. Only 3 percent of those were mass shootings (defined as more than four people killed). And when we factor in non-fatal shootings, that percentage is even lower. For example, Black males aged 15–35 have a firearm homicide rate 22 times higher than their White counterparts. And these stories of everyday tragedies, which mostly impact Black communities, rarely make it beyond the hyper-local news. As a result, countless people mourn in silence, weighed down by the stigma associated with violence, without ever having the opportunity to share their experience as part of their healing process. And the dominant narrative of gun violence as something that flares up every now and again, and otherwise affects only “bad people in gangs,” continues to shape the distorted picture of guns in America.

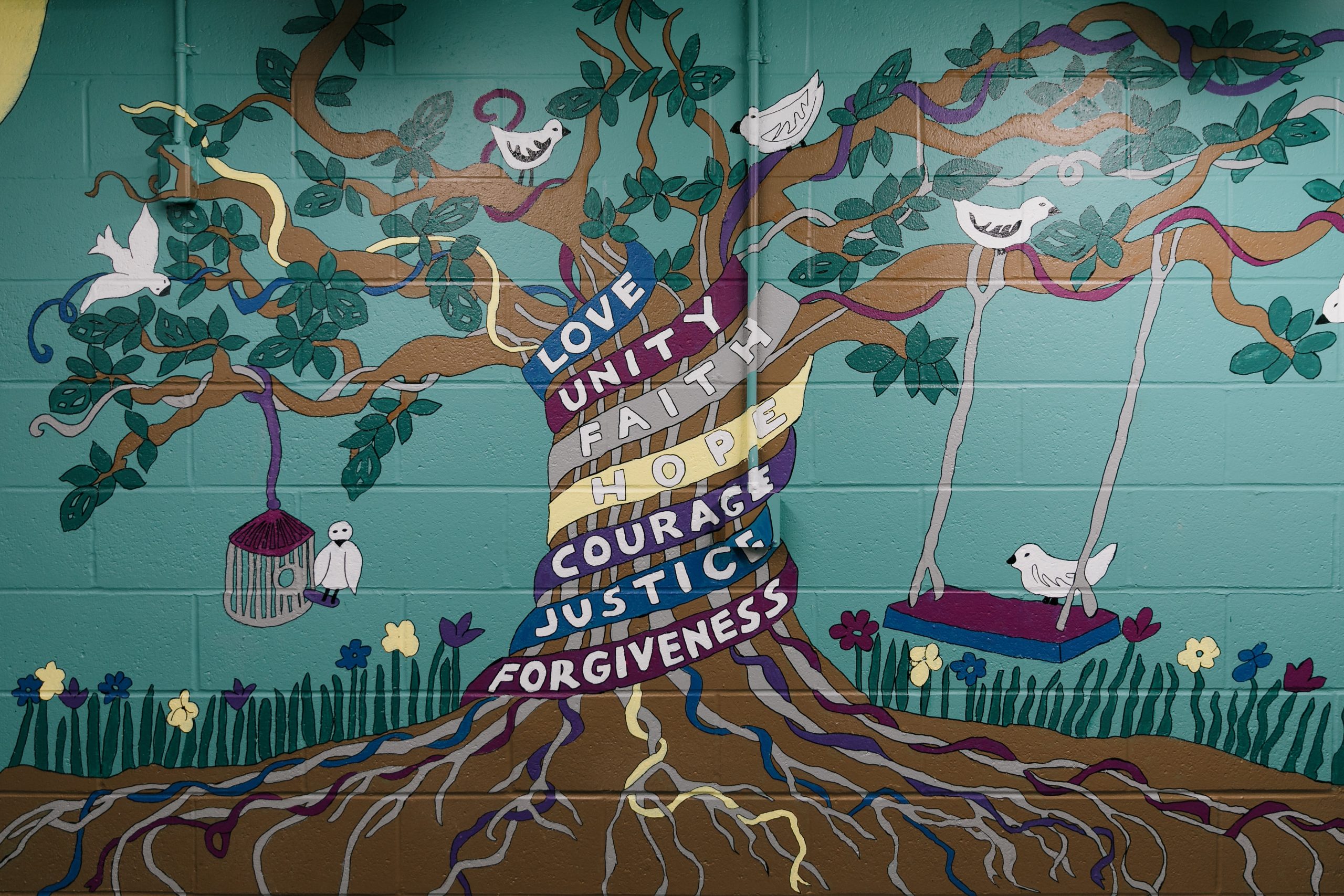

We need those closest to the pain to narrate the story of gun violence in this country. Continuing with business as usual, where media report on tragedy by recounting the facts and attempting to explain motives, actually serves to erase the immediate and ongoing trauma of those impacted, and removes the stories of healing and community strength that are so important to people’s lives. For this reason, in December of last year, together with Massachusetts General Hospital’s Center for Gun Violence Prevention and the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute, we launched the Transforming Narratives of Gun Violence (TNGV) initiative at Emerson College’s Engagement Lab. The three-year initiative invites communities and individuals with direct experience of gun violence to collaborate with media makers at Emerson to co-create stories in a range of forms (documentary, theater, VR, games, etc.) that go beyond the extractive trauma reporting that shapes the gun violence narrative in Boston and America. TNGV focuses on stories of healing, forgiveness, community harm, systemic racism, incarceration, and anxiety, as a means of both humanizing news spectacle, as well as placing each individual story into the context of systemic inequities. Last semester, a documentary studio course that included Emerson students, mothers of homicide victims, community advocates, and hospital employees produced a 20-minute documentary called Quiet Rooms, which tells the story of the journey from the family consult room in the hospital, known as the “quiet room,” where doctors tell mothers “their babies have died,” to the quiet rooms in the community where people come together to heal.

The painful truth is that too many Americans have wrapped themselves in a media cocoon, where every new story of gun violence is just hardening their ideological beliefs, reinforcing toxic narratives of renegade perpetrators or deserving victims. But the real problem is a culture of violence, amplified by a culture of guns, where the human stories of loss, desperation, resilience, and hope are glossed over. The gun, as Chaplain Clementina Chéry of the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute says, is just the weapon of choice.

It’s time to start asking questions: What does it feel like to resort to violence? What does it feel like to be a survivor? What does it feel like for communities of color to live in fear of both the reality and perception of guns in our neighborhoods? Until more people tell their stories, and more people demand to listen to those stories, nothing will change, because too many people will feel like nothing needs to change. It is going to take every single one of us to transform the narrative of gun violence in this country. Can we please get to work?

Eric Gordon is a professor of civic media at Emerson and the director of the College’s Engagement Lab.