Laura’s Law: New Protections Arise from Tragedy

Illustration by Leigh Wells/Ikon Images

After Laura Levis ’04 died unexpectedly in 2016, her husband, a former reporter for the Boston Globe, began a journey to tell her story and prevent other such tragic deaths. That journey resulted in Laura’s Law, which was signed into law by the Massachusetts Governor in January.

By Peter DeMarco

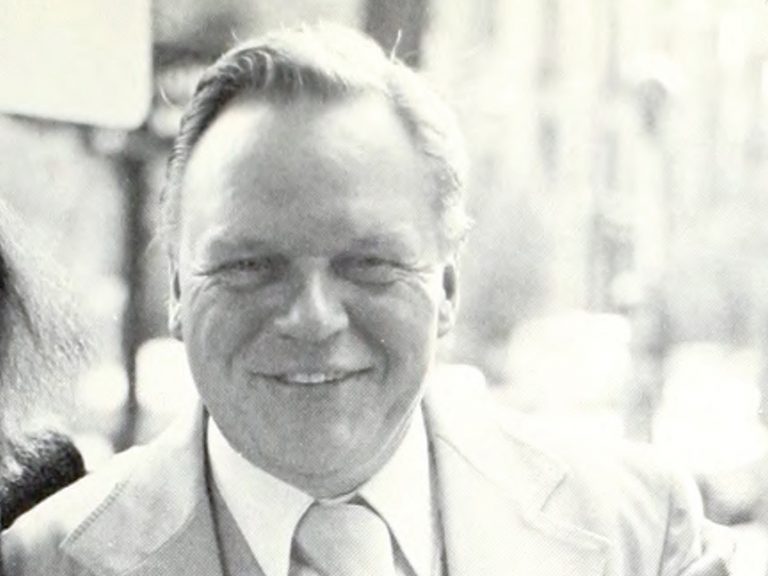

The picture of Laura I brought to the Massachusetts State House that afternoon was one of my favorites. We were in Scotland traipsing through the ruins of a castle, and as we climbed some steps, I turned back to see her smiling widely at me. Her brown hair flowed over her shoulders; the sleeves of her North Face hoodie comfortably dangled past her hands; she was aglow.

I had Laura’s picture enlarged into a poster board for the day’s ceremony. It was Friday afternoon, January 15, and Governor Charlie Baker was signing a bill created in Laura’s memory named “Laura’s Law.”

As I watched him put pen to paper in the flag-festooned Great Hall, so many emotions were rushing through me. It was incredibly bittersweet, but a moment that I think Laura herself would have been proud of.

I don’t know how many laws have been named after Emerson College alums, but now there’s at least one. Laura Beth Levis graduated in 2004 as a Writing, Literature and Publishing major. She loved Emerson and served as editor-in-chief of the Berkeley Beacon, an experience that propelled her into a career in writing and editing. She went on to work for Harvard Magazine, the university’s alumni publication, and then the school’s main communications office. She was young, intelligent, and talented. Her future was so bright.

If you live in the Boston area, you might know Laura’s story. I wrote about her death in a 2018 Boston Globe Magazine story called “Losing Laura.” Around 4:00 am one September morning in 2016, Laura started having a bad asthma attack (unfortunately, I wasn’t with her) and decided to walk to our local hospital’s emergency room just a few blocks away. But from that moment on, everything imaginable went wrong.

Of all the mistakes that morning, perhaps most glaring was how it was possible for this older hospital to lack a simple emergency-room sign above any door. Confused by this, Laura tried the wrong door, which was locked. Her attack overcame her before she could make it to the right door.

Her loss, at age 34, has been so hard for all who loved Laura. But what happened to her could have happened to anyone, which is why Laura’s Law had to be written.

“Laura’s Law will save someone’s life—I’m sure of that.”

Simply put, Laura’s Law will make every emergency-room entrance in Massachusetts easy to find and get inside. Officially known as “An Act Ensuring Safe Patient Access to Emergency Care,” it will establish first-ever standards for hospital ER signage, lighting, wayfinding, and the security monitoring of doors.

With such standards in place, I hope no one ever drives past an ER street sign tucked behind a tree, or goes to the wrong hospital entrance because it’s not clear where the emergency room is located. I hope that when someone is stuck at a locked door, there’s a panic button for them to push.

Laura’s Law will save someone’s life—I’m sure of that.

“When [Lt. Governor Karyn Polito] and I read [Laura’s] story, we didn’t read it as public officials. We read it as a mom and a dad, and a son and a daughter, and as a husband and a wife,” Governor Baker said at the bill signing. “We both thought at the time, ‘There ought to be a law.’”

More than four years after Laura’s death, and after a two-year fight to pass the bill, there finally is.

I’ve been asked what Laura would think of this. She was an incredibly determined woman, a real fighter—“Staten Island–tough,” she’d say, because that’s where she was from—and I thought of her strength often as I trudged through the frustratingly slow process of trying to pass legislation, let alone pass legislation during a pandemic. Certainly, she’d want no one else to endure what she had to.

When someone dies tragically, there’s so much focus on that fateful moment. But of course, that wasn’t who Laura was.

She was beautiful, and the funniest girl I ever met, making me laugh every day. She loved coffee, sleeping late, trashy TV, and our cats, and was the uber social planner, be it scoring tickets to a concert, nabbing reservations for a new restaurant, or planning our next weekend hike.

A fitness fiend, she worked out six days a week, and, though small in stature, she competed in a few women’s powerlifting competitions. Breaking gender stereotypes, she taught me how to lift weights—her favorite Instagram hashtag was #strongnotskinny.

Laura was intensely loyal to her friends and loved her family so very much, talking to her parents Bill and Georgia in New York City almost every day I knew her. She was passionate about writing and journalism, loves that blossomed at Emerson.

“She was just a powerhouse,” said Melissa Kaplan ’04, who was Laura’s second-in-command at the Beacon and years later sang at our wedding. “Just the smartest, savviest, warmest person.”

“Laura could have been any one of us. And now, because of Laura’s Law, every one of us will be helped.”

Though they were the same age, Kaplan said she learned so much from her best friend.

“It’s weird to say she was a mentor, but she definitely set an example for me,” Kaplan said. “She was wise but not stuffy, thoughtful, sensitive, and always on my side.”

Other college friends remember Laura’s skills as an “unflinching” interviewer. As a freshman assigned to the sports department, she tackled investigative pieces no one else would touch, said Beacon alum Paul LaRocco ’02.

Laura’s love for her hometown Yankees fueled endless debates with Red Sox fans on the staff. Even the longest nights in the Beacon’s old newsroom at 130 Beacon Street were somehow still fun with Laura at the helm.

Above all, said Paul Lurie ’04, Laura was always there for her friends. “She was the kind of person who would drop everything to help one,” he said.

One of Laura’s dreams was to work as a magazine editor, so she followed that path after leaving Emerson, becoming a writer and junior editor for Buckingham Browne & Nichols School’s communications department before moving on to a similar role at Harvard Magazine.

In the spring of 2016, she got a big promotion, becoming an editorial production manager for Harvard University’s Office of Public Affairs and Communications. In a matter of months, she’d made a huge impression, in part because she had so many talents, from writing to editing, from web content management to social media savviness.

“Laura was on the brink of taking us places we had only dreamed about and reaching goals we had been grasping at for almost a decade,” said her boss, Terry Murphy, editor of the school’s news website, the Harvard Gazette. “She was our one-woman dream team.”

Murphy told me she envisioned Laura becoming her successor one day. But as we know, that was not meant to be.

There isn’t a day that goes by where I don’t think of Laura and the amazing woman she was. But I take some solace in knowing that she has touched so many lives, and that so many people either will be or already have been helped because of her story.

Every newly hired 911 operator in Massachusetts is now trained on how to help callers who might be struggling to breathe. Nurses and doctors nationwide have been inspired to do their jobs better after reading a letter I wrote about Laura published in the New York Times.

Through the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, tens of thousands of people with asthma and their loved ones have been told that when an attack strikes, immediately tell someone, because you can’t anticipate the unexpected. They also now know to be cautious during something called “Asthma Peak Week,” the one week of the year that traditionally triggers the most attacks due to environmental factors.

It falls like clockwork on the third week in September, which is when Laura had her attack. If only she or I had known about it.

And now, there’s Laura’s Law. With hospitals focused on coronavirus treatments and vaccinations, the law likely won’t be implemented until 2022. But once standards are created, who knows how many will be helped when they rush to a hospital in the midst of a heart attack, a stroke, a drug overdose, or an asthma attack, and reach a doctor without a single delay.

When it was my turn to speak at the bill signing, I walked to the podium wearing a purple face mask, Laura’s favorite color.

“Laura could have been any one of us. And now, because of Laura’s Law, every one of us will be helped,” I said. “What would she say today? Knowing her, and how patience wasn’t her strong suit, probably, ‘It’s about freaking time this happened.’

But also, I think she would say, ‘I’m glad I didn’t die for no reason. I’m glad that through my death other people’s lives will be saved one day. And you know, that makes me feel pretty great.’”

When I finished speaking, I turned, and there was Laura’s picture on the easel. Like that day atop that Scottish castle, she was smiling at me. Under my mask, I smiled back.

Follow Peter DeMarco on Twitter at @peterdemarco