State of the Arts

The Impact, and Opportunities of the Pandemic

By Charna Mamlok Westervelt

On March 12, 2020, when New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio declared a state of emergency, shutting down Broadway and prohibiting large gatherings of people, producer Bonnie Comley, MA ’94, was three days away from opening her latest show, Tracy Lett’s The Minutes.

“We thought, ‘Oh, this will [last] a couple week,'” recalled Comley, who has produced more than 25 Broadway shows and who founded BroadwayHD.com in 2016.

We all know what happened next. We put on masks. We took them off. We stayed six feet apart. We installed plexiglass. We took down the plexiglass. We went remote. We had Zoom happy hours. We got vaccinated. We got boosted. We got COVID anyway. We moved gatherings outside when we could. We rescheduled and canceled all of our plans, it seemed.

Weeks turned into months. Months turned into years. Broadway finally reopened in the summer of 2021. And, The Minutes eventually did have its opening night—on April 7, 2022. Now, almost three years since COVID-19 burst onto the scene, changing how we approach nearly every aspect of our lives, many industries that had once been shut down are back. Some are even thriving. But the arts and entertainment industry—an economic catalyst—has been slower than most to return. What does this mean for the arts? And has the pandemic irrevocably changed the industry?

The Show Must Go On

“In the Broadway industry [alone], 100,000 workers were unemployed overnight,” Comley said of the 2020 shutdown. “Now, about half of the theaters are back and half of the shows are up and running…but the industry isn’t where it was in March of 2020.”

The National Endowment for the Arts and the US Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that “in year one of the COVID-19 pandemic, few areas of the US economy were harder hit than the performing arts.” Data analyzed by the National Endowment for the Arts show that “between 2019 and 2020, the US arts economy shrank at nearly twice the rate of the economy as a whole: arts and cultural production fell by 6.4 percent when adjusted for inflation, compared with a 3.4 decline in the overall economy.” The nonprofit Americans for the Arts reported that artists and creators were—and continue to be—among the most impacted segment of the workers in the US. At the height of the pandemic, 63 percent experienced unemployment and 95 percent lost creative income. The industry is recovering, but it’s slow going. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, arts, entertainment, and recreation jobs dropped from 2.5 million to 1.2 million between February and April 2020. As of September 2022, the number had rebounded to 2.3 million, which is still down 8 percent from pre-pandemic days.

Business As Usual?

When the pandemic hit, it was (mostly) business as usual for internet companies like BroadwayHD.com, which provides subscribers with exclusive access to digital captures of Broadway shows. (Digital captures are professionally filmed live, in a theatre, in front of an audience.)

“We didn’t miss a beat because we were already sharing [this content],” Comley said, adding that once Broadway was shut down, it became challenging to find quality content for the site. They looked to other cities and countries that were still producing live theatre. “We were getting content from Australia and the UK,” she said. “It was a frightening time, but it was also one of the busiest times.”

Like most, if not all, of the streaming services out there, BroadwayHD.com saw its subscription numbers rise during the pandemic, Comley said. And, as a result of these past couple of years, the Broadway community is more open to streaming their productions, she added.

“I think they see the value of streaming content—and see it as compatible content [now]. It’s not stream theater or go to the theater. You can have both,” she said. “There’s a whole different mindset in the industry [now], which is really exciting. I think they see the value of extending the life of these shows by capturing them [digitally].”

Likewise, David Howse, vice president for the Office of the Arts and executive director of ArtsEmerson, said incorporating a digital element into a live performance can augment and expand the audience experience. It also increases accessibility to the arts for those who may have never before been to the theatre.

“There’s nothing better than being in person and in proximity…[but] it’s incumbent upon us to not think of [online content] as competition, but in collaboration with,” said Howse, who also serves as vice president for institutional advancement at Emerson.

In the spring of 2020, like most arts organizations, ArtsEmerson was forced to cancel the last two shows of its season. But the staff quickly sprung into action to begin planning for the fall—a season they knew would be, by necessity, different from what they’d ever planned before.

“We asked ourselves, ‘What does it mean to be a presenter or a curator when you cannot come together? What does it mean to have the performing arts when you cannot come together?’” Howse said. “Not only was our health being challenged, but our identity was being challenged.”

Rallying around their deeply held belief that artists and the arts can help repair the world during the darkest of days, ArtsEmerson staff successfully presented a fully digital season in Fall 2020. “We had already been in conversation and in community with these artists and were ready to roll out a[n in-person] season. We just had to reimagine what it would look like online,” Howse explained. “I didn’t know how this was going to work. I wasn’t sure if anyone would log on.”

But they did. Now, going forward, Howse said he hopes to incorporate some of those digital pieces in future seasons, to continue to broaden the audience for ArtsEmerson shows.

“[The art world] is not better or worse, but there have been shifts.”

Leonie Bradbury, Distinguished Curator-in-residence, Emerson contemporary

Sound Check

In March 2020, Carolyn Snell ’97 was working as the tour manager for Alanis Morissette, getting ready to launch the singer/songwriter’s Jagged Little Pill anniversary tour.

“We had this full world tour planned and we kept pushing it back. It never felt like it wasn’t going to happen,” said Snell, who has worked in the music industry for the last 25 years as a tour manager and artist manager. “Finally in June we said, ‘We can’t continue to do this anymore.’”

Venues were closed. No one was touring. Anxiety levels were rising. “I was so worried about whether [live] events would ever come back,” she said.

As someone whose career was built on live events, Snell suddenly found herself without a music touring job.

As an interim measure, many musicians turned to live streaming home concerts. (And, in fact, Snell herself said she worked a virtual live event during her year off.) “A lot of artists that people wouldn’t have noticed or paid attention to before now had a platform,” she said. Especially early on in the pandemic, the ability to watch live performances remotely served audiences well. “We figured out how to shift a bit [during the height of the pandemic],” Snell said.

But as the pandemic dragged on, the patience of fans waned. So when venues reopened and bands started touring again, bands saw an outpouring of love and support from fans.

In July 2021, after a full year without touring, Snell began working with singer/songwriter Brandi Carlile as the artist’s manager. And while artists like Carlile partnered with streaming services to present live home concerts during the pandemic, Snell said she doesn’t anticipate live streamed events to remain as popular as they were in the early days of the pandemic.

“I think people want to be out [at live shows].

I don’t think it’s as exciting anymore to be watching a live stream,” she said.

And now? She’s thrilled to be traveling again. “Being able to tour the world—it’s been such a great gift and career path.”

Screen Time

Like live theatre and music, the film industry, which was hit hard by the pandemic, is rebounding slowly.

The US/Canada box office market comprised $4.5 billion in 2021, which was a 105 percent increase over 2020, although the market is still down substantially from pre-pandemic levels, according to the 2021 Motion Picture Association Theatrical and Home Entertainment Market Environment (THEME) Report. One area to see market growth, not surprisingly, was the home/mobile market. According to the THEME Report, the digital content streaming marketplace in 2021 accounted for 72 percent of the combined theatrical and home/mobile entertainment market, up from 46 percent in 2019.

It’s no surprise that the pandemic accelerated changes in how audiences consume television. While many people cut the cord to cable television long before COVID, the pandemic provided an environment rife for streaming. According to Hub Entertainment Research, nearly two-thirds of people said in June 2022 that they viewed free video on demand content on their televisions once a week, which is up from 46 percent of people in February 2020.

Likewise, the number of original television series and films exclusive to online services was up 15 percent from 2020 to 2021. And the number of films exclusive to online services increased by 90 percent from 2017 to 2021.

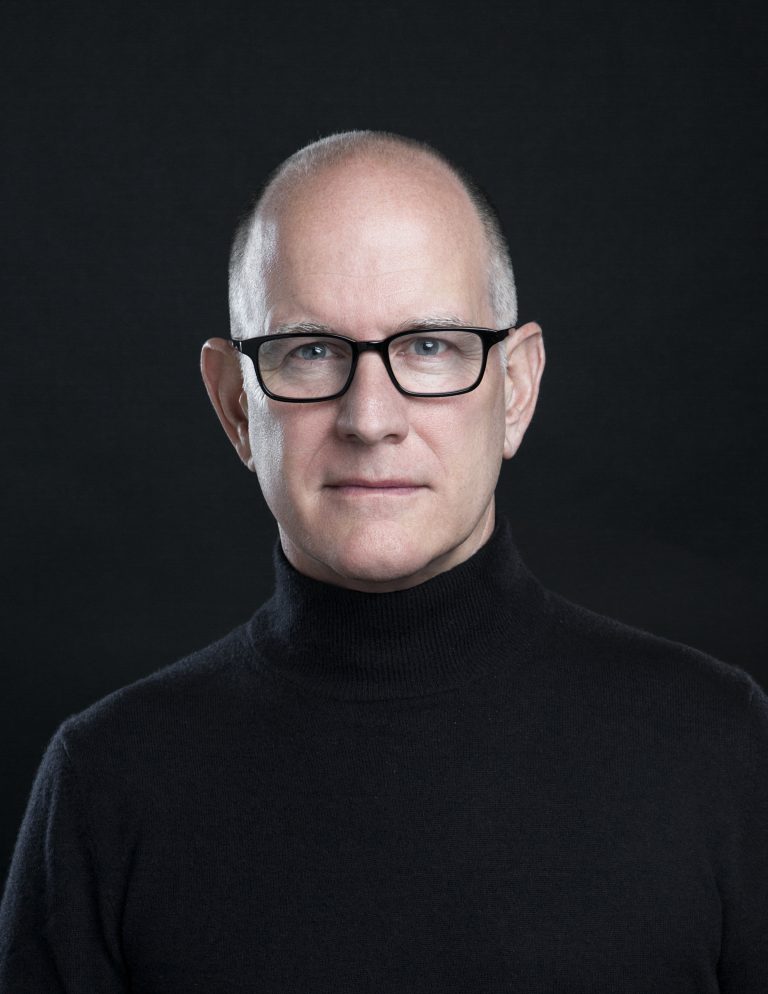

Mike S. Ryan, assistant professor of visual and media arts at Emerson and an independent filmmaker, said that when COVID shut down movie theaters, the power of the major online streaming services multiplied.

“The streamers dominated the exhibition space,” said Ryan, who has been making image-driven, character-based, arthouse-type independent films for the last 25 years, including the 2005 hit film Junebug, which launched actor Amy Adams’s career.

The rise in digital streaming has meant a decline in traditional film distribution. That change coupled with the decline in theatrical space is consequential for independent filmmakers and for the future of independently made films, Ryan said. As an example, he said the four films he was working on immediately prior to COVID were released “in a very diminished way because of COVID, because of diminished theatrical space.”

“I’m a small independent producer who’s really struggling right now in the shadow of [this streaming monopoly],” he said. “The independently financed film industry is in the most precarious situation it’s ever been in.” The result, he said, will be fewer American-made independent films. “It’s a real loss for American culture,” he said, adding that he predicts a rise in foreign-made films—quirky films from places like Scotland and Ireland.

A silver lining of the pandemic, Ryan said, was the rise in alternative streaming services, such as MUBI, The Criterion Channel, and Shudder, to name a few.

“One of the things that came out of COVID was that [people’s] taste palettes expanded [due to the rise in alt streaming services],” he said. “I hope we can maintain that curiosity by still trying to seek out those who are trying to make alternative forms of media and those who are representing alternative perspectives, counter to dominant ideology.”

Creating During COVID

Not only did audiences seek out new genres during the pandemic, artists and creators experimented, too, of course.

They had to. It’s in their DNA.

Artist EL Putnam–whose work will be on display this spring at the Emerson Contemporary Media Art Gallery–began experimenting with live streaming her performance art during the pandemic, said Leonie Bradbury, the Henry and Lois Foster Chair of Contemporary Art Theory and Practice and Distinguished Curator-in-Residence of Emerson Contemporary.

“She’s been very experimental and innovative. It wouldn’t have been created without those constraints,” Bradbury said. “That’s what artists are good at—making things despite the constraints.”

Bradbury should know. Early on in the pandemic, she curated a video and digital art drive-in project, in which more than 30 video and light-based artworks were projected onto the side of a building. The show, presented on August 14, 2020, in Salem, MA, was a success—200 cars came that night.

It wasn’t Bradbury’s first experience with large-scale projection, but it was the first time she’d curated a show for an audience who would experience it from inside their parked cars. “It’s so ephemeral [when] you project an image on a building. It does have a certain kind of magic to it,” she said.

Now that we’re no longer constrained to drive-in movie-style outdoor events, a new challenge has cropped up: artist availability. “All these postponed projects [from 2020 and 2021] are now happening. But the challenge is to get artists to commit now to exhibitions this year and next,” Bradbury said.

As she looks back on the past few years, Bradbury acknowledged the pandemic’s impact on presenting contemporary art. “[The art world] is not better or worse,” she said. “But there have been shifts. I wouldn’t put a value judgment on it.”

“It became absolutely critical for Emerson to say, ‘The arts are valuable. The arts are an important part of our culture. We have to find ways to continue to support artists and arts.'”

rob sabal, dean of the school of the arts

Support For The Arts

The Media Art Gallery, Emerson’s public-facing gallery curated by Bradbury, was closed beginning in March 2020 and through that summer. It was supposed to remain closed that fall semester, too (originally, the gallery was going to be used as classroom space, as part of Emerson’s de-densification plan), but it was able to reopen in Fall 2020 after all, underscoring the need for the arts, and a creative outlet, in difficult times.

“We were trying to be very creative and have some semblance of an exhibition program,” Bradbury said. “When I look back at it, we actually did quite a few projects; they just were not the traditional gallery [exhibitions].” She recalled one of her first meetings with Rob Sabal, dean of the School of the Arts, after the shutdown in March 2020. “He said, ‘Let’s make sure we keep artist opportunities going.’ It was really amazing to have that support,” she said.

Sabal said there was never any question in his mind what Emerson needed to do at that moment. “In that environment, it became absolutely critical for Emerson to say, ‘The arts are valuable. The arts are an important part of our culture. We have to find ways to continue to support artists and the arts,’” he said.

And Emerson did.

“We were able to support and commission work by fantastic artists,” he said, pointing to the Media Art Gallery’s curation of exhibitions that could be seen both inside and outside the building on Avery Street. “We tried to animate the city at a time when it was depopulated and remind people that Boston still was avital place, even though people may have been working from their homes.”

From the Media Art Gallery to light projections on the College’s Little Building, to Emerson Stage, which produced a fully online season in 2020–2021, to ArtsEmerson, to the many student films and projects that were created during the pandemic, the arts at Emerson persisted.