15 Lessons on Theatre from Maureen Shea

By Alex Ates ’13

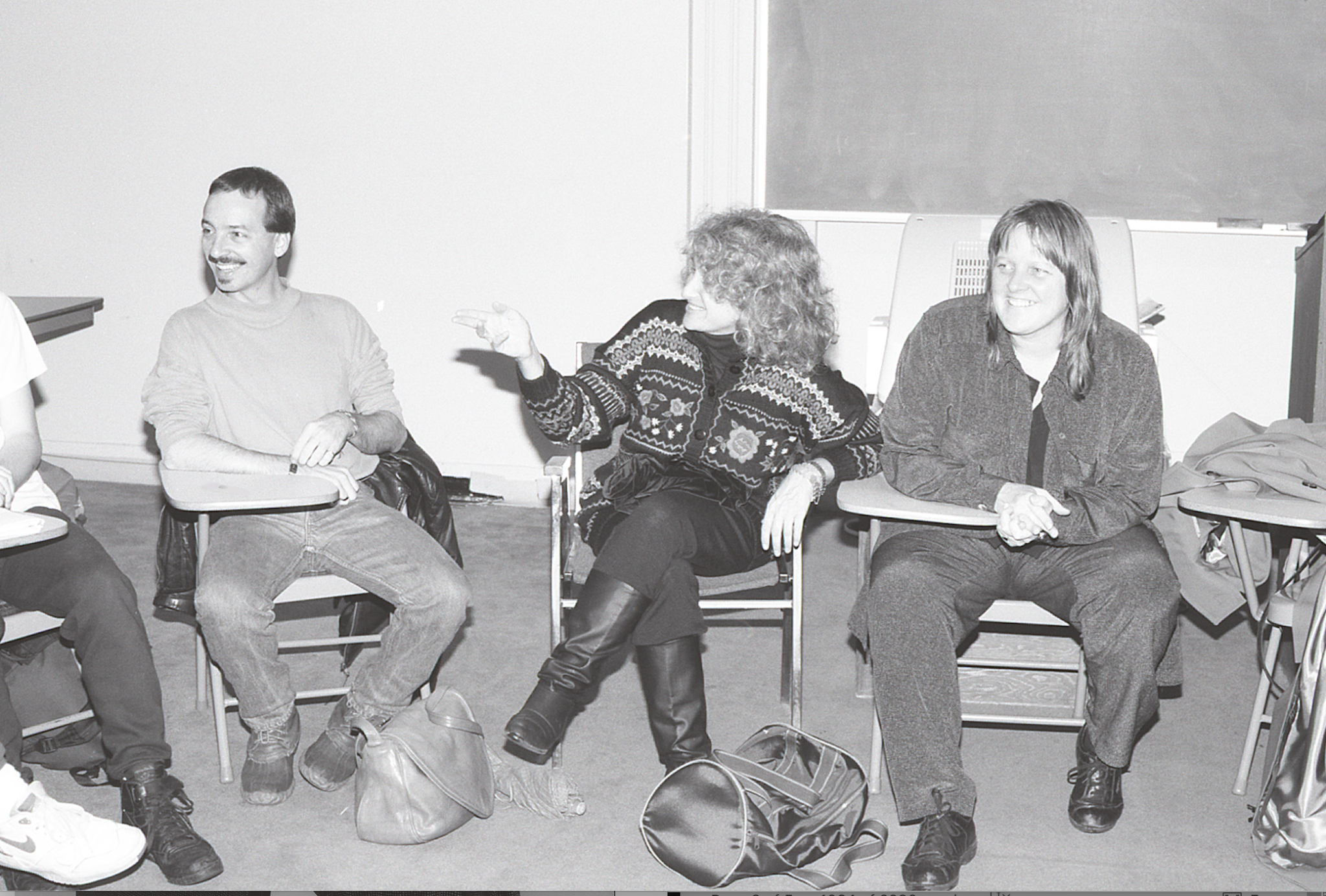

On March 1, Emerson College held a memorial service for Performing Arts Professor Maureen Shea, who passed away on September 20, 2022, at the age of 71. Alex Ates ’13 spoke at the service and later turned his remarks into an essay originally published by HowlRound Theatre Commons on April 6, 2023. This is an adaptation of that essay from howlround.com.

As I reflect on Maureen’s life and practice as an educator and artist at Emerson College, I am struck—and, frankly, stuck—by the profoundness of her force.

How, with words, can someone describe— truly describe—a mountain? Such is the challenge of honoring Maureen.

And so, I’ll use the tools my mentor taught me to make something here to share.

I’ll break it into beats and share some lessons that Maureen, my teacher, taught me.

1 The Potential of Expressive Arts

Maureen taught that heightened stories, lives, and circumstances are attainable through the tools of symbolism, naturalism, and poetry. Such is the potential of the expressive arts, hence the relevance of theatre schools.

2 Eulogies, Obituaries, and Plays

Eulogies are conversations and so, if I feel nervous or lost in my memorializing, I just need to settle into this conversation we’re having together about our love for Maureen.

This second lesson not only applies to eulogies, of course. Plays are also conversations.

3 Theatre is a Meeting House

The theatre is a “meeting house.” Maureen cleverly engaged the term after I was hired to teach theatre at a Quaker school.

Even in gold-leaf cathedrals of theatre like the Cutler Majestic, what makes this theatre reverent and relevant is that it is a palace for meeting: meeting yourself, ideas, hopes, and—most prerequisitely—each other. Theatre is about all the life around us—this, Maureen insisted on.

4 The Dignity of Being Real

Because theatre is a meeting house, we must always give characters “the dignity of being real.” Poetic humanism—or humanism as poetry—made Maureen a spirit-led director.

“I want people in a room, not actors on a stage,” she would say. Theatre as conversation is not a way of simplifying theatre-making, but it is a deeper calling that requires more listening from us artists. Before we have anything to say, we must listen.

5 Sentimentality and Self-consciousness

“Fear is the primary component of any actor’s life,” Maureen said.

“I’m here for you, I will catch you,” she said, “but you have to jump off the edge. Sentimentality and self-consciousness are the enemies of all art.”

6 Uncushioned Honesty

Maureen provided a valuable resource to Emerson: honest critiques. She was unintimidated in giving the gift of uncushioned honesty. This tendency was all the more radical as she operated in traditionally male-dominated spaces.

Maureen’s gusto was a gift. Her antennae for casting were never cliche, status quo, or safe. She sniffed out the potential of misfits, wallflowers, wounded warriors, backbenchers, and enigmas. Those who navigated her honesty walked away as more determined.

7 Work on a Play Like a Potter Works on a Wheel

Charge, carve, pound, push, and wrestle the play as one would earthy clay, she taught us.

Get it under fingernails, slap it, pinch it up, crush it down, cradle it, throw it on the table, and finesse its lines. Plays are not delicate ships in a bottle; they’re materials of dust and dirt because they’re matters of humans.

Plays are containers of energy and space. The more one fights, dances, and submits to the play, the more energy it will contain.

8 Maintain Absurdity

Maureen taught us to pivot between intense creative flows of highly caffeinated focus to boisterous, giddy, goofy guffaws.

I recall when Maureen taught the company of The Grapes of Wrath to sing a profane shanty of complaints during a particularly long tech hold. Imagine it: an ensemble of college actors singing, in harmony, profanity after profanity in the round. It was sardonic, offensive, unprofessional, and oh-so-delightful.

9 Fried Clams Are Gross

Maureen taught me that I can’t stomach fried clams. She took me to her favorite bayside shack to eat them. I turned green and even the thought of them gives me the heebie-jeebies. Although I found the clams abhorrent, taking me, a mentee, to share a meaningful meal was an act of hospitality and vulnerability. Maureen taught us to converse via communion.

10 We Carry Our Iterations

Maureen described my family as “wonderfully eccentric and yet so normal,” and I agree. My dad, an introvert by disposition, flowered in Maureen’s presence. My godmothers, both queer elders, were enchanted by a unique camaraderie.

We carry our iterations in all our interactions. The same thing that made me comfortable around Maureen is what made my family comfortable around her too.

11 Plays Are Metaphors for Love; Life Is the Real Thing

During a tech rehearsal for a show at the College, Maureen stood up, left the room, and turned a play over to me, her assistant, so she could be with her dying mother.

Counterintuitively, when she left, she pulled us closer.

“You will always be next to me as you were during one of the most profound times in my life,” she reflectively wrote to me years later.

By leaving the room, Maureen did the right thing. Plays are poems. “Listen to plays like you listen to people you love,” she said.

Yet, life is the essential, necessary, and permanent poetry. Plays are metaphors for love; life is the real thing. Don’t confuse the two.

12 Reject Gentrification, Avoid Pretension

Remington’s, a now-closed, blue-collar-Boston dive bar was a memorable place to conduct independent studies in the afternoon. Who can forget sipping a Guinness, smelling the stale wooden furniture, discussing Shakespeare, realizing a mouse was climbing over your foot, and then slipping out in the light of day?

For us, coffee was the fuel of the theatremaker; alcohol was the oil. Whether one drinks or not, by meeting at Remington’s, Maureen actively rejected the metastasizing gentrification of Boston by grounding my learning in a distinctly unpretentious environment. Taverns are also meeting houses. They’re also theatre classrooms.

13 Direct Like a Bowler

A regret: I wish I had gone bowling with Maureen. I don’t even know if she liked bowling, but I envision her as a proficient candlepin bowler, Massachusetts icon that Maureen was.

In addition to being a potter, Maureen— when directing—was a bowler. In the rehearsal hall, she would charge the play as a bowling ball charges pins. When all of the pins crashed, the sound was glorious, and it was a small miracle in its way.

When a gutter ball was thrown, it met the gutter with the same sheer force as it would the pins. Then, a roar, a laugh, a snap, a stomp—unhideable failure! And then, to the next roll, a new frame, a new game.

14 Theatre Is a Language and a Visual Art

Taking Mirta Tocci’s interdisciplinary Ways of Seeing class and Maureen’s Languages of the Stage in my first year at Emerson was an indelible one-two inducement into the alchemy of creative logic. Maureen and Mirta, a power couple of epic proportions, woke up an artist in me.

“Languages of the stage” was Maureen’s way of putting plays in the active oral tradition of theatre. Seeing plays as “languages” grounded our work among the songs of speech, the cadences of innate expression.

15 On Life, Love, Grief, and Plays

Last, a wonderful lesson: be grateful for the lives of the stage and hold to the urgent wisdom of the plays.

After college, Maureen and I corresponded about many plays. In recent years, we returned to Thornton Wilder’s mystical Our Town.

“The play encompasses all that is joyful and painful in life, as if our contribution to the universe, as human beings, is emotion and anxiety, feelings both joyful and painful, feelings that go with both community and isolation, life and death,” Maureen wrote to me right before the pandemic shutdowns.

Maureen continued, “Our Town, for me, captures that difference between humans and wild things…as Emily [from Our Town] maintains—we should live so, so that we can truly live.”

For Maureen, the words “live” and “love” were identical twins, if not interchangeable ones.

This is the MoShea manifesto: When we dignify stories on stage, we express our love for life, in stubborn defiance of grief. Maureen mastered that and dedicated her life to teach it to us.

Thank you for that last lesson, Maureen.

That last note.

That last direction.