Stop Making Sense

Living In An Age of Disinformation & Misinformation

Illustrations by Lincoln Agnew

By Erin Clossey

In 2015, Ben Collins ’10 was a reporter for the Daily Beast covering “dumb, stupid internet things,” like the guy who posted that Limp Bizkit was going to do a show at a Dayton, Ohio, Shell station on 4/20 and hundreds of people showed up. Demonstrably false? Absolutely. Viral? Sure. Dangerous? Meh.

Then one morning, Collins woke up to the news that the girlfriend and colleague of his Emerson classmate and friend, Chris Hurst ’09, had been fatally shot while reporting on air in Virginia.

Searching for information about his friend online, he was presented with lie after lie: Hurst and his girlfriend, Allison Parker, were crisis actors; Hurst secretly worked for the CIA; Parker didn’t exist.

“They were just railing on this dude for being alive, for existing. And that was the top thing you would see on the internet when you looked him up, at the worst moment of his life,” Collins recalled.

“Our goal is to find the people who are skeptical, or give people the ability to talk through [misinformation] with their friends who have maybe started to fall down that path.” —Ben Collins ’10

Ever the reporter, Collins began contacting the people who were pushing the lies on YouTube videos. He’d let them talk for a half-hour, and then he’d tell them he knew Hurst personally and explain why none of what they were saying could be true. “And they were like, ‘Well, that’s just what I believe.’ And I was like, ‘Well. OK.’”

“Those very people in that very algorithm that was pushing that stuff to the forefront took over our politics the next few years,” said Collins, who today covers extremism, disinformation, and the internet for NBC News. “And I just kept following; I never stopped writing about it or following it or covering it.”

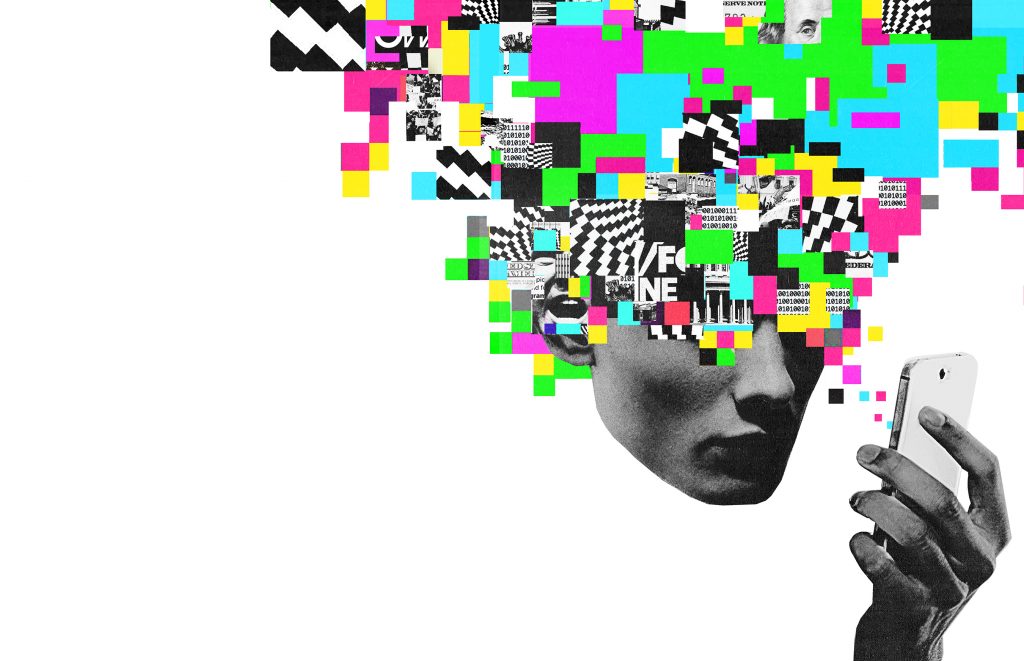

Conspiracy theories and those who spread falsehoods are nothing new (see: Landing, Moon). But over the past decade, our information ecosystem has become a fertile floodplain of disinformation (intentional dissemination of lies) and misinformation (unintentional). A November 2021 report by The Aspen Institute concludes that disinformation and misinformation in the US is jeopardizing our ability to solve some of the world’s greatest challenges, such as climate change, COVID-19, or political polarization.

Virtually every major news event today is either complicated, distorted, or, in some cases, manufactured by bad information. At best, it’s laughable and absurd. At worst, it tampers with free elections, incites insurrection, and leads to thousands of preventable deaths from COVID. It comes from campaigns orchestrated by foreign states, homegrown extremists fomenting division and hate, cable news channels, and even your own aunt.

And we’re all part of it, said Whitney Phillips, MFA ’07, a critical media studies scholar at Syracuse University, and, beginning in June, assistant professor in the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism and Communication.

An Unnatural State

When you’re dealing with a false claim or bad information, you can’t just focus on the misinformation or disinformation itself.

“You have to look at the broader system that spread or even incentivized that information,” said Phillips, author of This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture (MIT Press, 2015), and, with Ryan M. Milner, You Are Here: A Field Guide for Navigating Polarized Speech, Conspiracy Theories, and Our Polluted Media Landscape (MIT Press, 2021), among other titles.

“It’s not just the false claim that’s the issue. It’s how has that false claim been incentivized by our economic informational structures? Where does it go after you encounter it? Who does it end up impacting? Whose bodies does it end up affecting?” —Whitney Phillips, MFA ’07

By understanding the larger context, she said, you can begin to assess the critical dynamics at play, such as the differing roles of right-wing and center-left media, each of which has its own history and needs to be considered on separate terms, including the kind of harm it causes.

While center-left, mainstream media has norms and values that are problematic in many ways, she said, on the right, a parallel information ecosystem has emerged over the course of the last 50 or so years that has developed its own norms and values, along with a distinct nomenclature and “enemy systems.” And for a variety of reasons—historical, political, and economic—the right-wing media landscape has more rapidly intensified.

Phillips prefers to talk about the media landscape using an ecological framework—specifically, pollution. It allows us to think about systemic, root causes of harmful false information and not get hung up on any one piece.

“Because it’s not just the false claim that’s the issue,” she said. “It’s how has that false claim been incentivized by our economic informational structures? Where does it go after you encounter it? Who does it end up impacting? Whose bodies does it end up affecting?”

There are three metaphors Phillips uses to talk about our polluted media ecosystem.

Redwoods stand in for network infrastructures. Just as the giant evergreens pass along nutrients and resources, as well as disease, through interconnected root systems across entire forests, what happens in one part of our network swiftly spreads to another part.

Phillips uses hurricanes to talk about the energies that fuel narratives. Many factors determine a hurricane’s category, its duration, and where it makes landfall. How fast a story or piece of information spreads, and its impact, depends on the historical, sociological, and economic factors feeding it. Finally, land cultivation refers to human choices, and how everything everyone does in our ecosystem has an impact, often independent of motive.

“Those three lenses help you have bigger conversations about these issues….you can situate and position yourself within that ecology and better understand what we need to do to mitigate some of the problems that we currently face,” she said.

Working the Beat

As journalists covering disinformation, hate, and far-right extremism, Ben Collins and Christopher Mathias ’08 are standing in the center of the media ecology.

Mathias, a senior reporter at HuffPost, describes his beat as “where extremism intersects with people in power,” and his work focuses on ideologies of hate in the military, law enforcement, government, schools, and medicine. Mathias’s two most recent stories, as of this writing, were about the ideas, positions, and high-profile, democratically elected guests common to both the America First Political Action Conference (AFPAC), a White nationalist gathering held in Orlando this year, and, eight miles away, the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC), a highlight of the GOP’s calendar. We live in an era in which a QAnon conspiracist and COVID denier like Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene is welcome at both.

“I think one of the pitfalls of this beat is that because it’s often so egregious and so wild and kind of fantastical, sometimes outlets fall into the trap of covering it just for entertainment’s sake, which I don’t think is responsible.” —Christopher Mathias ’08

Covering this beat requires a tricky balance, said Mathias, whose family has been doxxed and threatened as the result of his work.

“I think one of the pitfalls of this beat is that because it’s often so egregious and so wild and kind of fantastical, sometimes outlets fall into the trap of covering it just for entertainment’s sake, which I don’t think is responsible,” he said.

“For example, it’s not news what the [Neo-Nazi group] Atomwaffen Division[’s] latest propaganda reel is. That’s something you could study and definitely keep an eye on, and when they are in the news, you can…put the propaganda in its proper context. I think it’s just a fine line. You’re trying to write about these people without mainstreaming their ideas.”

Another way to responsibly cover disinformation is to take the Deep Throat approach.

“What’s behind this? Is there money behind this? Is there dark money behind this?” Collins, of NBC News, says he and his colleagues always ask. “And then victims…if you highlight how these people hurt people, you’re going to get people to understand.

“You have to come at this as ethically and morally as possible, and then work backward from there. And occasionally, you will find something that is just too stupid or silly or funny not to dunk on; and you’ve got to do that too, because otherwise you go nuts.”

Journalism Professor Paul Mihailidis, assistant dean in Emerson’s School of Communication and director of the graduate program in Media Design, said there’s a lot of “vibrant and interesting and critical” journalism being done today, and reporters have more tools than ever before to do their jobs.

But most journalism in this country is for profit. Social media platforms have driven down advertising rates for local news outlets that were never robustly resourced, further gutting them, Mihailidis said. Big media companies such as the New York Times and the Washington Post have stepped into the breach with content that isn’t fake news, but also isn’t always as nutrient-rich as individual communities need in a functioning democracy.

“When we opt into these platforms and technologies that aren’t prioritizing a deep engagement with information, the journalism outlets, they take on the values of the media companies within which they publish. And that can be really problematic,” Mihailidis said.

“When we opt into these platforms and technologies that aren’t prioritizing a deep engagement with information, the journalism outlets, they take on the values of the media companies within which they publish. And that can be really problematic.” —Paul Mihailidis, Journalism professor

Feature, Not Bug

The January 6, 2021, Capitol insurrection was a shock to many Americans watching it unfold in real time, but it didn’t surprise Whitney Phillips and her fellow media scholars one bit.

Beginning with Gamergate in 2013–2014, when a lot of “reactionary energy” had been kicked up online by White men in the video game space who were outraged by women and people of color entering what they saw as their domain, and continuing through every US election cycle since, academics and activists have been trying to convince Facebook and other social media platforms to put in some guardrails against rampant disinformation, harassment, and hate speech. They were ignored.

“You look back and you’re like…‘Where were you in 2013 when interventions could have been possible?’ Now there’s nothing that they could do, really,” said Phillips, who recently gave testimony to the January 6 Committee. “It’s frustrating, because it’s not surprising. They had plenty of time to prepare for all of this, and they didn’t; they chose not to.”

The problem isn’t that our information systems are broken, Phillips said, it’s that they’re working exactly as they were designed to work: to allow for the fastest spread of information to the greatest number of people.

Part of that is in service to an American ideal of a free and open exchange of ideas, she said, but a lot of it boils down to greed. The more that gets shared, the more these platforms get paid.

“We’re dealing also with a capitalistic kind of economic system that doesn’t just allow for, but incentivizes the spread of pollution,” Phillips said. “So long as our networks continue to work the way they have been designed to work, we will not ever, not even a little bit, be able to get out of this cycle.”

What Now?

So, if fake news and disinformation are everywhere, polluting every corner of our media ecosystem, and the kind of energy that most efficiently travels across our networks is the very energy that rips civil society to shreds, and our system, as built, has little to no incentive to do anything about it, where does that leave us?

Phillips says it’s too late to tinker with our existing networks—we would need to restructure from the ground up. But, she hasn’t given up on future generations.

She’s putting her Creative Writing MFA to work on a book for middle-grade readers called Thinking Ecologically About Social Media, due out early next year from Candlewick Press. It uses Phillips’s environmental metaphors to empower young teens to think about their role in the ecosystem, with a focus on mental health.

“It’s not just about giving them tools for how to engage in group chat with their friends…but it actually speaks to what I said earlier, that you’ve got to cultivate a different pattern of mind in younger people so that they understand their place within the online ecosystem, and how to make those systems healthier, how to build different systems,” she said.

While we’re waiting for the next generation to build a new system, reporters such as Collins and Mathias are continuing to hold those in power accountable.

When Mathias began covering extremism and disinformation at HuffPost in 2017, it was one of the few news organizations dedicating resources to the beat. And those that were, were primarily digital publications.

“Now, the Washington Post has people, the Times has people, and you’ll notice that a lot of news organizations are hiring disinformation/misinformation desks, which wasn’t really a specific thing years ago,” he said. “I was talking to a reporter in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, who has been assigned to covering extremism in Pennsylvania, because it’s such a pervasive problem there.”

Collins said his work will never reach those who stand to gain a lot from the disinformation wars. “Our goal is to find the people who are skeptical, or give people the ability to talk through stuff with their friends who have maybe started to fall down that path,” Collins said.

Mihailidis said he thinks we need to “unseat” the platforms from their perch as the primary way we engage with the world and pull people from behind the “veil of technology.”

It’s easier said than done, Mihailidis said, because society is already so self-segregated and burdened with inequities. But in his classes at Emerson, and through the Salzburg Academy on Media and Global Change, which he directs, he teaches a “care-based” media literacy that reprioritizes dialogue, talking across differences, and finding ways outside of Facebook and other online media to be with one another and build community.

Because the way our networks are designed is not how we as humans are designed, he said.

“When you bring people together and give them time and space to talk and learn about each other, you inevitably see the commonalities between their worlds,” Mihailidis said. “I’m constantly surprised that we do this in [real life], and how the mediated cultures that we exist in now, they force us to make generalizations really fast. It’s not the way that we are built to work.”