The Tricks and Flips That Build a Community

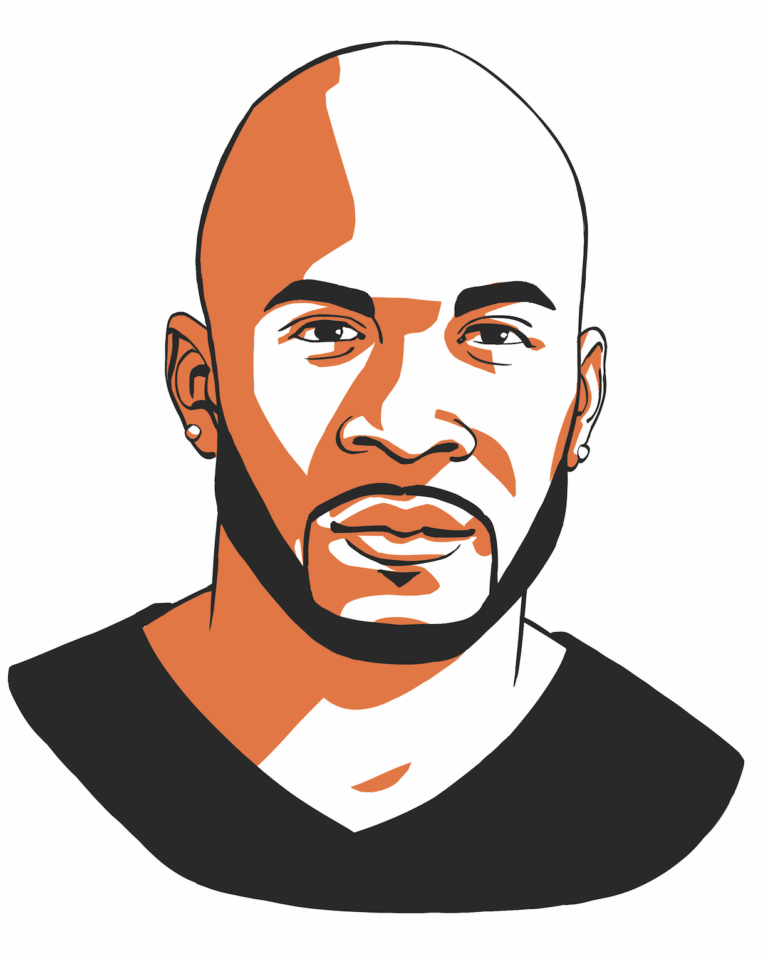

It’s been a couple of decades since Benjamin Anderson Bashein ’98 has hopped on a deck himself.

But for the past three years, the self-described “middle-aged guy…with bad knees” has helped bring skateboarding to underserved communities across the country as executive director of The Skatepark Project (TSP), founded by legendary skater Tony Hawk.

“If you play basketball or baseball, which is fantastic, you’re joining a team. If you skateboard, you’re joining a community,” Bashein said. “I think it’s the perfect sport for kids who maybe are a little different, or a little more creative…who think and see the world a little bit differently.”

The Skatepark Project, which began as the Tony Hawk Foundation in 2002, provides grants, technical assistance, and advocacy support to local organizations working to bring skateparks and skating to underserved communities across the US. Over the past two decades, TSP has helped build nearly 700 skateparks in all 50 states, serving more than 9 million young people a year.

As executive director, Bashein meets with corporate partners, such as Vans or Converse, to get projects built; he advises cities on how to incorporate skateparks into their parks and recreation plans; and he works with The Skatepark Project’s ambassadors — pro-skaters and other influencers — who help raise the profile of the sport and the work that the organization does.

Sometimes the job is incredibly moving.

In June, Bashein and TSP celebrated the opening of the Tyre Nichols Skate Park in Sacramento, CA. Nichols grew up skating in that city, and after he was fatally beaten by Memphis police in January 2023, his family and friends began raising money to create a skatepark memorial in his name. By March, The Skatepark Project came on board.

Hundreds came out for the opening, where corporate partners gave away skateboards, helmets, and pads to local kids who otherwise wouldn’t be able to afford them, Bashein said.

“It was a nice moment to create a permanent memorial for him. We’re working now on getting a similar memorial park built in Memphis,” he said.

The foundation takes on projects of all scopes, sizes, and stages. Bashein said that very often they work with young skaters and their families who are holding bake sales to raise money for a park. But increasingly, they’re partnering with municipal governments in major cities, including Atlanta, New York, and San Francisco, who look to The Skatepark Project for help in building safe, inclusive, and accessible parks.

That hasn’t always been the case. Twenty years ago, many cities and towns (and their residents) balked at building skateparks, believing they attracted “troublemakers and hooligans,” Bashein said. But over time, local officials and others have begun to see the physical and social benefits of skateboarding.

Those benefits are legion, according to Bashein. It’s financially and physically accessible, as sports go, requiring just a skateboard and a little pavement. It builds creativity, resilience, and perseverance — not to mention community.

“Everybody is welcome in the skatepark. You’re competing against yourself, and…you’re at a skatepark that’s full of people of different ages, and sexual orientations and races, who are passionate about the same thing, each bringing their unique style to their skating,” he said.

The sport has exploded in popularity in recent years. As with other activities that can be done outdoors and/or alone, it gained a huge following during the early days of COVID, and got a further boost when skateboarding made its Olympic debut at the 2020 Tokyo Summer Games (played in 2021), Bashein said.

“Right now, the fastest growing group of skaters are young women,” he said. “There are amazing subcultures. There’s a Queer skate subculture, and there’s a Native skate subculture. There are skate communities in every city all across the country.”

Bashein came to Emerson in the mid-’90s thinking he would train as an actor or a dancer, but he soon learned that his greatest talents lay elsewhere, and he gave up any Broadway dreams. However, through his involvement with EAGLE (Emerson’s Advancement Group for Love and Expression) and other student groups, Bashein began volunteering with a range of Boston-based organizations and developed a new outlet for his creativity.

“I ended up doing a DIY, make-your-own-major situation, where I was doing a lot of studying and writing about how the arts could impact political issues and social change, and found my passion there,” Bashein said.

From the moment he graduated from Emerson (in just two years), Bashein has worked for organizations at the intersections of art, culture, celebrity, and social issues, raising awareness and money and building partnerships across industries to effect change.

“I think culture can move the needle on social issues in a really powerful way,” said Bashein. “I just think the visibility that [it has], the visibility to bring these issues alive, is really powerful.”

He spent a number of years working with contemporary artists and fashion and media brands in New York before moving to Los Angeles in 2018 to serve as vice president of partnerships and communications for CORE (Community Organized Relief Effort), actor Sean Penn’s disaster preparedness organization. Then, in 2020, he added action sports to his portfolio when he joined The Skatepark Project.

Since 2016, Bashein also has consulted for brands in the arts and fashion industries, helping them create social impact campaigns, which he said allows him to have a broader influence. But whether he’s working with artists, designers, brands, influencers, or pro-skaters, Bashein said he’s taken his Emerson education with him— not just the fundamentals of communication, but also something less tangible.

“It cultivated a creativity, and a bravery, and a willingness to do things differently, and a desire to live in a really diverse environment. There are so many different people with so many different passions there,” Bashein said.

“It’s a good place to be weird, and I think there’s a real value in that. There’s not enough of that in the world.”