In (Banned) Books We Trust

By Kara Baskin

Books — those tactile landscapes of ideas, opinions, foreign worlds, and fresh perspectives — possess the singular power to galvanize, inspire, and provoke. And today, book bans are skyrocketing in school districts across the country. Free speech organization PEN America has chronicled more than 4,000 instances of book removals since it began tracking in 2021. Many banned books illuminate gender identity and sexuality, including Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe and Flamer by Mike Curato, which were the two most banned books in 2022.

“We’re in a very dangerous place in this country,” said Kim McLarin, interim dean of graduate and professional studies at Emerson. “I used to say that we were on the verge of creeping authoritarianism, but I don’t think it’s creeping anymore. I think it’s sprinting…I think it’s not an overstatement to say our very democracy is under threat.”

Today, Emerson is at the forefront of supporting free speech, despite these chilling movements toward censorship and suppression. Notably, McLarin and Writing, Literature and Publishing Professor Wendy Walters organized a first-of-its-kind Banned Book Readathon in May 2022.

Students read from and browsed banned books in the lobby of the student center at 172 Tremont as part of a National Day of Action coordinated by the Freedom to Learn Network and the African American Policy Forum. Books included Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Beloved by Toni Morrison.

“Students are furious when they hear what books are being banned. If you show students a list, these are some of their favorites—and that any book would be banned is very concerning to them,” said Walters. “We were so happy that students showed up and brought their favorite book. It was very moving.”

“We wanted to raise awareness of what’s happening not only across the country, but even here in a progressive, liberal haven [like] Massachusetts,” McLarin added. “It can happen here, and it is happening here. People need to be aware of that, too. We can’t be smug about living in what we believe is a liberal paradise, because it’s everywhere. We can speak up, we can teach, we can challenge false narratives, and we can be politically active.”

In fact, Massachusetts has seen a dramatic surge in book challenges and disturbances, according to the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners. Combined formal and informal challenges, objections, and disruptions have nearly quadrupled in just a year, it reports, including requests to remove typically mainstream titles such as The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain.

As such, McLarin and Walters chose the busy student center as a deliberately visible spot, aiming to attract a broad swath of students who could also pick up donated banned books while just passing through.

“In terms of Emerson being a thought leader, we wanted this to be a community event. We left a note on the box that said, ‘Please help yourself to a banned book,’ because that’s one of the best ways to counter repressive measures. Make the stuff available, read it out loud, get people participating, stand up, and show that you’re not on board with that kind of silencing,” Walters said.

A Longstanding Problem for Modern Creators

While the sharp increase in censorship is getting more media attention lately, book-banning has a long history in the United States. In fact, it began in Massachusetts when Thomas Morton published The New English Canaan, which was banned by the Puritan government in 1637 as overly critical. Since then, censorship has persisted, from Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe during the Civil War (too pro-abolitionist) to James Joyce’s Ulysses (too sexually explicit).

Walters, who specializes in African American literature, confronts book-banning in her classes, both from an ideological standpoint but also because Emerson students are tomorrow’s creators—and, if we’re not careful, she said, tomorrow’s suppressed voices.

“What are we afraid of? Who is afraid of the truth, the historical truth, the literary truth, all the different truths that might run counter to what I see as a white supremacist narrative of this country’s history and founding?” she asked. “Emerson is a place where students see themselves as creative, as having new ideas that they want to put into the world—creative ideas that they want to bring to life in such a wide variety of forms, whether it’s writing, filmmaking, acting, politics. These are people who are going to write stories, novels, memoirs, nonfiction, narrative nonfiction, and they don’t want someone to tell them they can’t say something.”

As executive director for library and learning at Emerson’s Iwasaki Library, Cheryl McGrath’s job is becoming increasingly complicated in an age of disinformation, propaganda, and artificial intelligence. A huge part of her role is helping these creative students dispel truth from fiction — and to be courageous in their literary and creative choices.

“As a librarian, the thing I want to see Emerson students go out and do is write books from all the perspectives and then publish books from all the perspectives,” she said. “[If you] trust that there are a variety of perspectives in the world…you will find your audience as a creator, as a publisher, and [you can] be brave in your own creativity and in your own choices that you make.”

“Publish the stories that you think need to have their voices heard,” she added.

Books As A Safe Space, Now More Than Ever

Books harness the capacity to transform and to comfort: Take it from author Simon Jimenez, MFA ’17, a graduate of the Creative Writing program. His dystopian fiction has earned praise for its elegant prose and its complex subject matter, including violence and non-normative sexuality.

“I chose to write books because I love how intimate it is compared with other art forms, where it’s a direct interaction between you and the person experiencing your art. A book requires someone to have read the words, and thought about the words, and to create a world inside their own head,” he said.

As such, McGrath sees libraries as a refuge and a haven, especially now.

“Librarians act as a reader’s advisory, in which we direct people to the book that they need. I think where this gets complicated is when minors are involved…especially if you have a child who has a deep internal need to explore their identity and a family and social structure that doesn’t support that. The library can be a safe place for them,” she said.

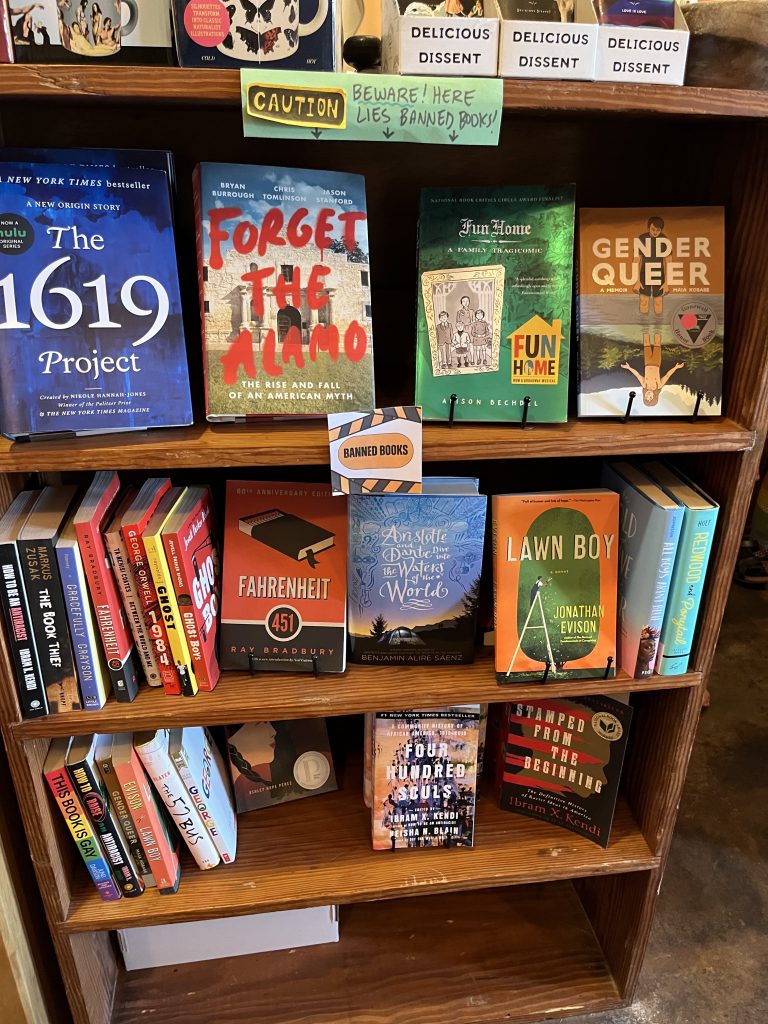

That’s partially why Mary Ann Cicala ’00, MA ’09, and her wife, Thais Perkins, launched Reverie Books in Austin, TX. The 1,000-square-foot shop has blossomed into a literary and social hub since opening in 2021, elevating queer voices and writers of color.

“Being rabble rousers, storytellers, and community builders, our first thought was lifting marginalized voices. Part of it makes sense because we’re a queer family here in South Austin who already had a love of reading books that push on social issues,” said Cicala, who graduated with an undergraduate degree in Theatre Production and Management and, later, a graduate degree in Communication Management.

At her bookstore, New York Times bestsellers sit alongside Lambda Award–winners, which is intentional.

“Somebody who might just be going in for a bestseller is sort of accidentally exposed to something they wouldn’t necessarily be exposed to if they go into a big chain,” she said. A portion of sales proceeds benefit local nonprofits that support marginalized communities. For instance, during Pride Month in June, profits supported counseling services for LGBTQ+ youth.

In addition to supplying books to local schools, Cicala and Perkins hire paid interns from nearby Crockett High School. The program started because teens were so comfortable among the shelves that they didn’t want to leave, so the pair put them to work. A key part of the job? They select titles for Reverie’s young adult banned-book club, where teens gather to discuss divisive works under threat.

The space has evolved into a sanctuary for young people who feel like outsiders in the conservative state. Actor Elliot Page’s new bestseller Pageboy: A Memoir, about his journey as a trans man, is one recent hit. Another is The 1619 Project, the deep dive from New York Times journalists on slavery’s legacy and how Black Americans’ contributions shaped early US history. Texas Gov. Greg Abbott banned the text from being taught in schools.

“People come into our space and they love it. They walk in, and they just see themselves. We’ve had so many people just fall apart in very sweet ways when they feel seen, heard, and represented,” Cicala said.

So far, the community has been supportive — “Austin is a slice of blueberry pie in a red state,” she said — but there’s a constant threat of a negative review or online missive that could damage the business’s reputation. But the daily interaction with customers, many of whom consider Reverie a refuge, outweighs any fear for the pair.

“Recently, a woman of Mexican heritage came in and found a book on the history of the Mexican American experience in Texas and just wept openly. She was so thrilled to have found something that spoke some truth,” Perkins said. “And young people come in and they’ll go, ‘My gosh, I never thought anything like this could exist.’”

Protecting such moments is essential, said Walters, who plans to hold another banned book event this year. It’s about protecting creative freedom, but also about protecting people and ideas, because future generations depend on it, she said.

“We have to keep showing up, being present and being vocal and never assuming that those who want silencing and repression will win,” Walters said. “You have to resist whatever appears to be a dominant repressive force, and I think [Emerson] students want to do that. Nobody wants to think that the books that they love won’t be available to their children and grandchildren.”