Discovering His Calling

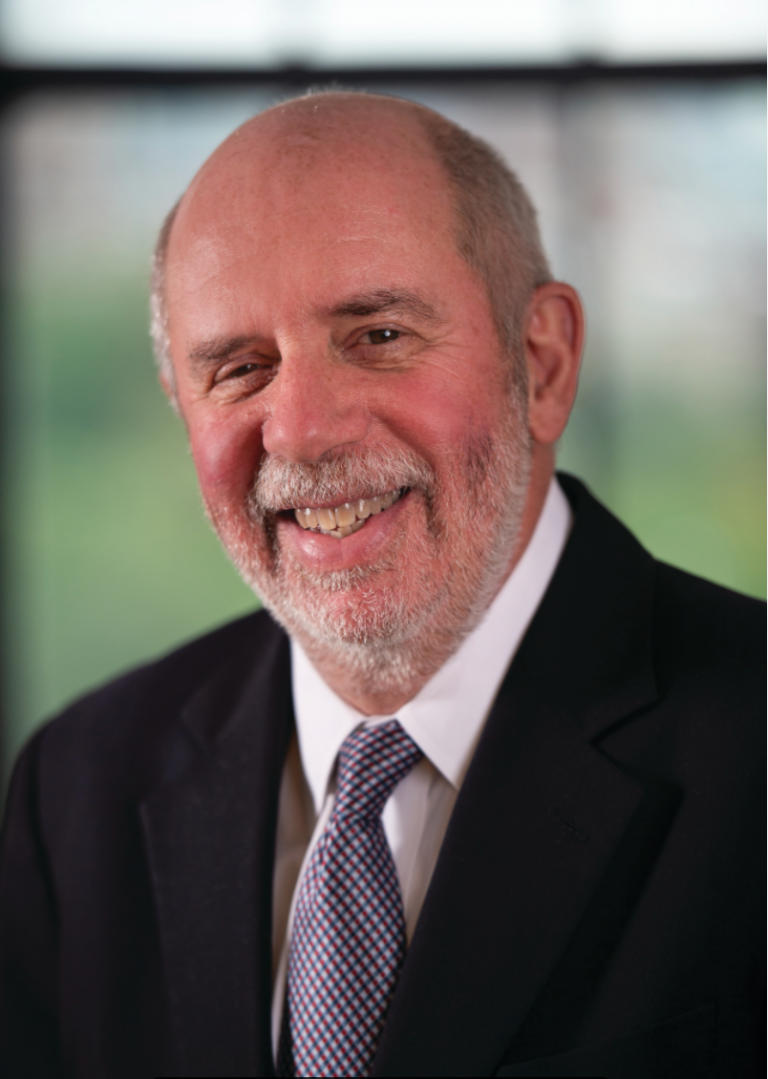

What are our moral obligations around artificial intelligence (AI)? How can this technology be used responsibly and ethically? How can we ensure AI will benefit humanity? These are just some of the questions that Rev. Dr. Nathan C. Walker ’98 is exploring as the principal investigator of the AI Ethics Lab at Rutgers University.

Walker, an award-winning First Amendment and human rights educator, has long been dedicated to freedom of expression—not only exercising his own personal freedom, but also helping others express their beliefs.

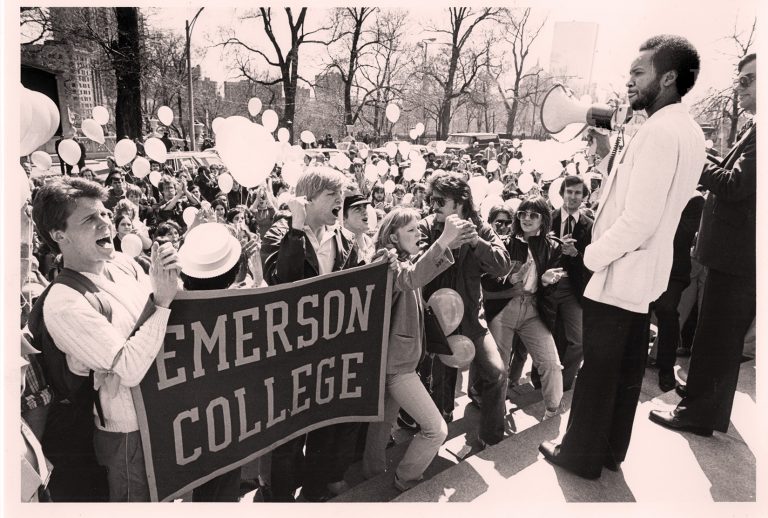

First Amendment law is about the five freedoms: freedom of speech, press, religion, petition, and assembly. These freedoms are ultimately about human expression. “That’s been a through line through cultivating my voice at Emerson, [and] engaging in that liberty of conscience by working in both art spaces and religious spaces,” says Walker.

Today, he’s applying that expertise in individual and human rights to the emerging issues surrounding AI. As a visiting researcher at Oxford University’s Institute for Ethics in AI and a contributor to the Munich Convention on AI and Human Rights, Walker seeks to exercise the practice of moral imagination in which a person pictures themself in an ethical dilemma about AI in order to understand competing viewpoints. He also applies this method in the courses he teaches, “AI Ethics and Law” and “AI and Society” at Rutgers, and it is a focal point for his sixth book, Moral Imagination: Ethics & Empathy in the Age of AI, forthcoming in 2025.

“I’m so grateful to be a part of the responsible tech movement and to engage with the moral issues of our time,” he says.

Thirty years ago, when Walker began at Emerson as a musical theater student, he couldn’t have imagined the twists and turns that his path would take. Yet he connects much of his work and life’s journey back to Emerson.

Walker’s experience at Emerson was deeply meaningful and foundational to what would come next. For instance, as a student, he and other Emersonians worked with children in a local after-school program, where they collaborated to adapt and put on plays such as The Grinch Who Stole Christmas and Raggedy Ann and Andy. “It was about building their self-confidence, helping them find their voice—which is so much of my experience at Emerson,” he says.

Later, during a semester at Emerson’s Kasteel Well, it wasn’t only the European experience that was life-changing, but it was also how his friends supported and cared for him on a deeply personal level at a time when he was searching for his biological father. “They were fully invested in the adventure,” he says. “These amazing peers of mine were there with me at every stage. I have a deep, deep sense of gratitude for Emerson, for holding me in care.”

His life’s journey, however, was also affected by what he calls a gritty story. After college, he moved to Carson City, Nevada, where he taught at Western Nevada College. “The theater arts program was really vibrant,” he says.

While there, he looked into adoption opportunities, because he was interested in becoming a parent. “I remember the moment when the agent clutched the cross around her neck and said, ‘You don’t meet the definition of family,’” he says.

“That was an extraordinary experience,” he says. “I realized Nevada wasn’t a place where [a gay man] could build a family.”

As ugly as that realization was, he can trace his focus on human rights, fundamental rights, and the First Amendment back to that moment.

After his brief but consequential stint in Nevada, Walker moved to New York, where, in 1999, he helped build New York University’s first online academic program. When the Twin Towers fell on 9/11, Walker had been volunteering with a local Unitarian Universalist church, a community he was drawn to because of its openness and respect for individuals. “I realized this was where my interest was. It was more than belonging and being in a community that upholds the inherent worth and dignity of every person. It was about me seeking out a new vocation,” he says.

So, he began ministerial training at Union Theological Seminary while working on his doctorate in First Amendment law at Columbia University. Walker was ordained in 2007. “It was an extraordinary time…to ensure that religion was about helping people, not hollering at them,” he said.

From there, Walker was called to be the senior minister of the First Unitarian Church in Philadelphia. During that time, he took a sabbatical year at Harvard Divinity School to further his study of First Amendment and human rights law, focusing on legal restrictions on religious expression.

As a minister, as an educator, and in all facets of his life, Walker has worked hard to ensure that everyone is free to express themselves. “My ultimate objective is to create spaces that allow each of us to have an ethical empathy for those with whom we disagree,” he says. “If we deeply seek to understand one another—and understanding does not imply agreement—we might be able to see that the core values that motivate each person [are] actually part of a network of ethics that we all share.”

Walker credits Emerson, and its motto, “Expression Necessary to Evolution,” for providing the underpinnings for his life’s work.

“Emerson created a really powerful foundation for me to engage in this multifaceted vocation, because it was a training ground for me to build my self-worth, to know I belong, to find my voice, and to recognize that freedom of expression is deeply connected to our collective evolution.”