The Risks and Rewards of Diplomacy

By Paul Pegher

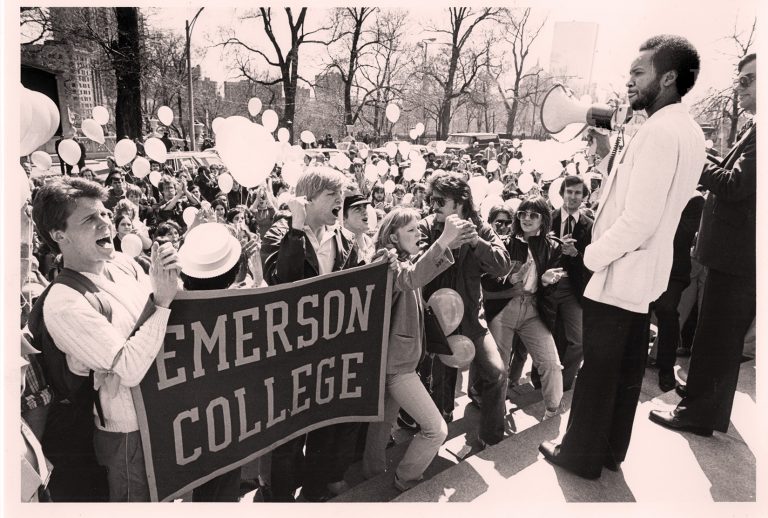

For the first 25 years of his life, Aaron Snipe ’94 lived and worked within a six-mile radius: from his hometown in Arlington, MA; to Emerson College; to Suffolk Law School; to Boston Common, where he worked as a US National Park Service ranger.

But for the last 20 years, as a foreign service officer for the US Department of State, Snipe’s world has stretched through time zones and war zones. Working under seven different Secretaries of State, Snipe has served assignments in Ethiopia; Iraq (three times); Japan; and the United Kingdom, where he is currently the spokesperson for the US Embassy in London.

Snipe never planned on a career in the foreign service. But his experience during law school as an exchange student in Japan stuck with him. “For a Boston kid six miles from home, going to Japan was a very, very big deal. I was fascinated by the culture, and I wanted more. I wanted a grassroots experience,” he recalls.

Two years later, he was about to take a job in a district attorney’s office when, to the surprise of his family and friends, he instead changed paths and decided to teach English in Japan. “I didn’t tell anyone I applied for that job because they wouldn’t have understood why I spent all this time and money on a law degree,” he says. When he told the hiring attorneys about the opportunity abroad and his sense of conflict, one said, “Go to Japan…you may never have this space in your life again.”

With that advice, Snipe took a calculated risk—one that led him to the countryside of Kagoshima. And the experience was transformative. Snipe began to truly see the perspectives of other people, reflect on the cultural dynamics of the world, and understand his place in it.

He returned home and, at the suggestion of a friend, took the Foreign Service exam just weeks before September 11, 2001, and just blocks from Ground Zero—a tragedy that firmed his resolve to pursue a career in foreign affairs.

Like all diplomats, Snipe shifted every two years between service and training at home and vastly different assignments abroad. He began in Ethiopia in 2003, where he planned an international HIV/AIDS conference with a Peace Corps volunteer named Praya, who is now his wife and mother of their two children. In 2008, he went to Al-Muthanna, Iraq, where he learned the “internal diplomacy” between the US military and foreign service, who seemed to speak different languages, and the external diplomacy of working with farmers and

artists—not just government officials—to build and strengthen their institutions. In 2010, as deputy spokesperson at the US Embassy in Baghdad and newly wed to Praya, the couple often found themselves holding tight in the bathtub during rocket attacks, garbed in their helmets and bullet-proof vests.

While assigned to the US Embassy in Tokyo, their son and daughter were born. Snipe was drawn back to Iraq in 2019, this time without Praya or a strong US military presence. He was a cultural attaché, which meant once again working with citizens, not politicians. It was professionally gratifying but personally difficult, he says, with his family being in Japan.

Regardless, Snipe recognized the necessity of diplomacy—a force more important than military. As he wrote for “This I Believe”—one of his many published articles and essays and one that was once cited by then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton— “…in the toughest neighborhoods on earth, when the front lines of war transform into the main streets of peace and stability, diplomacy must be first on the scene. It is neither

convenient, nor always safe, to practice diplomacy in such places, but it is absolutely necessary if America is to successfully engage the world.” (Snipe also shared this sentiment at the Tufts University Fletcher School upon receiving the Edward R. Murrow Award for Excellence in Public Diplomacy in 2014.)

Today, in his role at the US Embassy in London, Snipe explains that diplomacy with allies is more complicated than it is in the toughest places. “Alliance relationships actually require almost more attention than relationships with our adversaries, because we know each other so well; the stakes are so high; we have a lot of history,” he says. “But there are times when we disagree. And managing relationships within a family is sometimes more complicated.”

Like any relationship, listening is critical and humor goes a long way, Snipe says. Last year, the US Embassy posted a video on its social media—a spoof of Snipe getting sacked for backing England during the World Cup. Snipe likens that video, and the other spoofs they’ve done, to “reading the room and having enough understanding and savvy to know when and where good humor is good diplomacy.

Today, Snipe finds inspiration in what he calls “that sweet spot of diplomatic engagement,” where the work is about bringing people together—whether it’s farmers, artists, and community builders in Iraq; famine relief workers in Ethiopia; or townspeople in Sheffield, England, who for 80 years have laid wreaths at the graves of US airmen killed in WWII, a ceremony for which he recently represented the United States.

“My career at the State Department has been punctuated by 20 years of things just like [that ceremony]—moving events that may not make the national press or be at the commanding heights of foreign policy. But they are the grassroots of what I do, and what I am proud to do representing the United States

of America.”

In His Own Words

As a spokesman, statesman and all-around cross-cultural communicator, Aaron Snipe ’94 has accumulated many stories and insights over two decades. Here are just a few, in his own words.

How two years in Japan set the stage for foreign service

“If you are American and you grew up in America and America is your only experience, you may think because America is so big and so diverse, that you sort of understand the world.

But I’m telling you from my own lived experience that I don’t think that’s the case. When you start learning another language, speaking another language in a foreign country, when you start to see the perspectives of people.

The first year I was there, I read 53 books—books ranging from Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville to other important titles that I thought I should have read, but hadn’t until then. I also read a lot about Japan and studied Japanese. I became very reflective about the world and my place in it.

It was during those two years that a friend of mine said, ‘You know, you love public service. You’ve never been in it for the money. The money is not important to you. You love foreign languages. You love foreign cultures. Clearly, you’re going to love traveling for the rest of your life. Why don’t you consider, you know, taking the Foreign Service exam and becoming a U.S. diplomat?’

And I said, ‘You know I’m a terrible test taker. I’ll never pass it, but yeah, when I get back to the States, I’ll find time to take the test.’”

On taking the U.S. Foreign Service Exam

“Of course, I put it off for years. I moved to New York and got a job in the financial services industry. Then I got a better job in the financial services industry and was just sort of making my life in New York.

But all the while I kept thinking, ‘This is not what you’re supposed to be doing.’ And then finally—and this is an important point— I had already been signed up for the exam before 9/11. So that tragedy was not the impetus to taking the exam. During that summer of 2001, I had decided I’m going to do this. I’m going to sign up for this exam and I’m going to see if I can do it.

And then 9/11 happened and just a few weeks later, I took the Foreign Service exam just a couple of blocks away from Ground Zero. I mean, I could see Ground Zero from there.

I took the test, and walked out wondering if I failed or passed. It was the most interesting test I’d ever taken, and I just thought, ‘Let’s see what happens.’ I learned months later that I passed, and then they brought me down for what they call the oral assessment, which is essentially like an eight-hour interview where they put you in groups to see how you interact and give you a writing test and a briefing test and an interview. And then they send you off and to sort of mill about for an hour, and then they bring you back and they tell you whether you’ve passed and then you undergo your top secret security clearance, which can take eight months or up to a year or something like that. And then you’re in, and you begin your first two years of training.”

The first tour in Iraq: A bomb attack during Barack Obama’s Inauguration

“One of the most memorable moments of my time in Iraq was January 20, 2009, when I was posted at a forward operating base. It was Inauguration Day, and we were all going to the chow hall to watch Barack Obama be sworn into office.

What we did not know is that insurgent elements had decided to launch a rocket attack targeting the chow hall because they knew that there would be a maximum amount of U.S. troops and other personnel watching the ceremony.

I didn’t go to the chow hall because I had work to do, and we had a TV in our office. I remember Barack Obama getting up to take his oath and saying, ‘I, Barack Hu…’ and he didn’t get the ‘Hussein’ out before rockets started landing on the base. So we grabbed our vests, our helmets, and we ran to the duck and cover shelters as rockets just rained down for the next five minutes.

Thankfully, they had terrible aim and no one was killed. But that was sort of my reality for a year.”

On taking diplomatic risks on social media…in good humor

“If you’ve seen any of the social media that we’ve done here at the U.S. Embassy to the U.K.—such as the spoof video of me getting fired that we produced during the World Cup games last year— it may not seem risky to you. But in the State Department culture, it’s an outlier—definitely not something you would expect from the U.S. government.

However, it does resonate the respect and friendly competition between the countries. We’ve actually done three or four of these, and they’re still available on the embassy’s YouTube channel.

The funny thing is that with all of those, I didn’t ask permission to do them. I’m a 20-year veteran of public diplomacy, and I think I’ve got a pretty good sense of judgment on these things and a pretty good read of the host country and the host country’s sense of humor and how these things will land.

I mean, there are a million ideas that never make it to video because we’ve decided [if it’s] a bit too edgy. We have to be sensitive and at times very careful. But at the same time, we can still follow our vision, if we can read the air.

There’s a lovely adage in Japanese—kuuki o yomu, which means “to read the air” and those who can exhibit that are considered highly skilled. It is a skill that all diplomats must have. You can’t make it in this business if you can’t read the air, if you can’t read people. Or the country.”

Shifting from the war on terror to the battle for truth

“I began my State Department career in 2003, and so, in some ways I’m the generation of diplomat that was defined by—we don’t call it this anymore—the global war on terrorism. During the Cold War, we had a lot of Russian-speaking diplomats. After 2001, many of us learned to speak Arabic and Farsi and Dari and Pashto. And a lot of us would spend years of our career in places like Afghanistan or Iraq. So I came up in that post-9/11 era where we were singularly focused on combatting or containing forces of terrorism.

Today’s platform of diplomacy is different. In part it is shaped by ‘great power’ competition. U.S./China relations are at a very difficult moment as these two giant economies and influential nations are trying to find a way to coexist.

We’re also faced with challenges to the international rules-based order, as exhibited by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. And so, maybe if I had to come up with a line, it would be that this next period is about great power competition and the preservation of the international rules-based order. To put it another way: Can a country just invade another country, and then lie about it, and do so with impunity?

That is why the Russia incursion into Ukraine is so critically important. And it’s why countries like Poland, and Lithuania, and Estonia, and all these other countries are sitting there worried, saying, ‘If Russia can so blatantly flout international rules-based order with Ukraine, what does that mean for other countries?’

Both the great power competition and the preservation of the international rules-based order have impact on structures to address climate stability, structures that help us coordinate on human rights, the structures that protect free speech and journalism, the gross education, and just sort of all those things that we think like, well, yes, of course, everybody agrees with that. OK, maybe the Taliban doesn’t, but they’re an outlier and yet understanding that, too, is really important.

I think that this next period is going to be about the United States and like-minded allies leading on that, trying to preserve that, so that we don’t have countries that are going their own ways and violating those rules-based orders that have helped bring prosperity to so many over the decades.”

On US-UK diplomacy: It’s complicated

“Some may think that relationships with our adversaries are more complicated than with our allies, or even that allied ties can run on autopilot. They are so wrong.

As someone who has worked both in Japan and the UK—what I consider the premier Trans-Pacific relationship and our most important Trans-Atlantic relationship—I believe alliance relationships require more attention than relationships with our adversaries, because we know each other so well, the stakes are so high, and we have a lot of history. But, there are some times where we disagree on things, and managing relationships within a family is sometimes more complicated.

My tenure here in London, over the past almost three years, has come at arguably one of the most pivotal moments for the United Kingdom in its history: Brexit. Americans were tracking this, so it had meaning for our relationship. We’ve also now reached the end of the Elizabethan era, with the death of her late majesty, Queen Elizabeth the Second. That was a tectonic event. In the next couple of months, we’ll have the coronation of King Charles—a beginning of another era, which I think is really, really important.

At this moment in time, the United Kingdom is trying to figure out who they are in relation to the EU, to the United States, and the world. So I see this as a critical moment in the US-UK relationship—one where it’s really important to have diplomats from both sides who are staying close to one another, and working through the challenges that both countries are facing. There are real and substantive issues—confronting Iran, our coordination on Russia and Ukraine, economic response to China. This stuff has really deepened our relationship during this period.”

About the U.S….

“And so, let me just make one last point on this. It’s not just the United Kingdom that’s going through a question about who they are. It’s also America, right? I’m talking to people from other countries all the time, and many are asking me, ‘What the heck is going on back in America?’

While I speak on behalf of the United States government, I am often asked to interpret what’s happening back in America. From our response to COVID, to the Black Lives Matter and Me Too movements, to the January 6 crisis—all of those things. I’ve been asked every conceivable question—even why Will Smith slapped Chris Rock, and what about Harry and Meghan— all those things come up. It’s been fascinating to help British audiences better understand the tectonic shifts that we too in America are going through.”

The Three-Dimensional Chess Game of Diplomacy

“If there was a criticism of the US State Department’s system, it is that we move people around every three years, and just when you’re getting good, just when you’re getting the depth, we send you off to another country. And so, some believe we should keep people in countries for longer periods so they can really dig in and understand things.

But I think there’s real value in moving people around, and I’ll give my own situation as an example to explain why. Later this year, I’m going to go back to Tokyo as my onward assignment and I think that’s a smart move by the United States government because I have the subject matter expertise. We are confronting China. We’re confronting a threat from North Korea. I’ve got relevant experience in these portfolios that would be very useful.

Now, you could say, ‘But you’ve been away in London. You’ve been doing something completely different.’ Well, when we talk to the Japanese, we don’t want to just talk to them about Japan-only issues. We want to talk to them about the NATO partnership. We want to talk to them about instability in Europe, vis-a-vis Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. We want to talk to them about the impact of Brexit. We want to talk to them about a whole host of issues.

And so, in that way, it actually does make sense to have diplomats who get out of their area of expertise, get a little Trans-Atlantic experience, and then take that back to the Trans-Pacific relationship. I’m really excited to go back and focus on Japan, but also bring all the things that I’ve learned in Europe, at a really pivotal time between the US and UK, because that will also benefit the work that I do in Japan.

One of the natural offsprings of globalization is our interconnectedness, and obviously, we see and feel that on supply chain issues. We certainly felt it a lot during the pandemic. But, one of the things that’s been gratifying to me, especially when we’re talking to our allies, is we have so much to talk about, right? It’s not just the things that we, America and the UK, care about that only relate to each other. Well, yeah, that’s important. But, when we are trying to gather a coalition of nations to push back against Iran’s elicit nuclear program, to push back against Russian military aggression, or economic coercion by the Chinese government, how do we do that?

Well, we can’t do it alone. We have to talk to other countries about these things. And countries that have huge economies like Japan have interests in lots of different areas. If you’re only having a one-way or a two-way conversation, then you’re missing all of the other areas of interest that you could be engaging on. And so, I do think that it is three-dimensional chess wherever you are in the globe.”

On “The Last Three Feet”

“Of course, it’s been incredibly gratifying to negotiate a bilateral agreement with a foreign government. That stuff is great. But the stuff that fuels me—that makes me feel like ‘Oh, I love this job!’ —is the stuff at the last three feet.

Here’s an example: One of the best parts of being in the UK, as a public diplomacy person, as the spokesperson to the embassy, is that I can be at Number 10 Downing Street for a reception where I meet the Prime Minister, and then, a day later, I can drive three hours up to Sheffield for that last three feet of diplomacy. That’s where I recently attended a memorial service to commemorate 10 US airmen whose plane crashed there during World War II, 79 years ago.

As I sat there in the front pew of the church, I marveled that this crowd of people—from very young to very old—are remembering our fallen airmen almost as if they were killed last year. I mean, you can’t not be moved by the idea that the good people of Sheffield spend their own resources and time every single year to remember the Americans who served and died. I then had the incredibly moving honor of laying a wreath of flowers, picked from the Ambassador’s garden.

I look at that moment, and think that my career at the State Department has been punctuated by 20 years of moments just like this—moving events that may not make the national press. There were similar moments in Ethiopia and Iraq, where I was doing real on-the-ground work with local officials, farmers, business people, artists, and activists—not politicians or military officials. They may not be at the commanding heights of foreign policy, but they are the grassroots of what I do, and what I am proud to do representing the United States of America.”

On meeting his wife in Ethiopia, and honeymooning in wartime Iraq

“I met Praya in Ethiopia, back in 2005. I was working at the United States Embassy on my first overseas tour, and assigned to organize the International HIV/AIDS Conference in Ethiopia. Luckily for me, the Peace Corps sent Praya —who has a master’s in public health and extensive experience in HIV/AIDs work—to help me plan the conference. We became really good friends and then of course, she went back to Washington and I stayed in Ethiopia. We reconnected when I returned to the U.S. and started dating before I went on my first assignment to Iraq.

When I returned, we got engaged and married before I went back to Iraq, this time with Praya. We didn’t want to be separated again, so she said, ‘Look, I’m willing to quit my job and follow you to Iraq, and we’ll start this life.’ I think she and I had envisioned a regular sort of diplomatic assignment, but it was the middle of the Iraq war, and I had studied Arabic and I felt like I could continue to be really, really useful. And so, she did the very brave thing by saying, ‘I’ll go with you.’

It was a foundational and important year early in our marriage. When we traveled to different places, we had to be in our full bulletproof vest and helmets. We even experienced a number of rocket attacks on the embassy. There were times where during a rocket attack, we’d be in the bathtub just waiting for the duck and cover alarm to stop, or the rocket attack to stop. That’s a pretty intense experience if you have it for yourself, which I did when I first served in Iraq. But, when you’re with your spouse and you’re both holding each other, waiting for the rockets to stop, it’s quite another experience. It wasn’t like that every day but we did it together, and got through it together.”