The Staying Power of the Liberal Arts

Illustration by Monica Chu

Alex Pyne ’23 intended to major in Communication Studies at Emerson.

But an assignment in his first-semester writing course—in which he analyzed A Charlie Brown Christmas through the lenses of mechanical reproduction and memetics—changed and clarified his path. “[The assignment] was a lot of fun, and I realized it was similar to the kind of work that I wanted to continue doing while at Emerson,” Pyne said.

What he wanted to study was “political messaging within popular culture and how mass media operates within the political economy.” The only problem was there wasn’t such a major at Emerson. So he created his own: The Politics of Culture and Media. It’s a liberal arts major that exists at the intersection of the liberal arts, communication studies, and media studies.

Critics of the liberal arts have long deemed it a discipline that is impractical and out-of-touch, but in today’s world where politics, messaging, media, and popular culture are more intertwined and omnipresent than ever, one would be hard-pressed to find a major more relevant, or urgent, than Pyne’s.

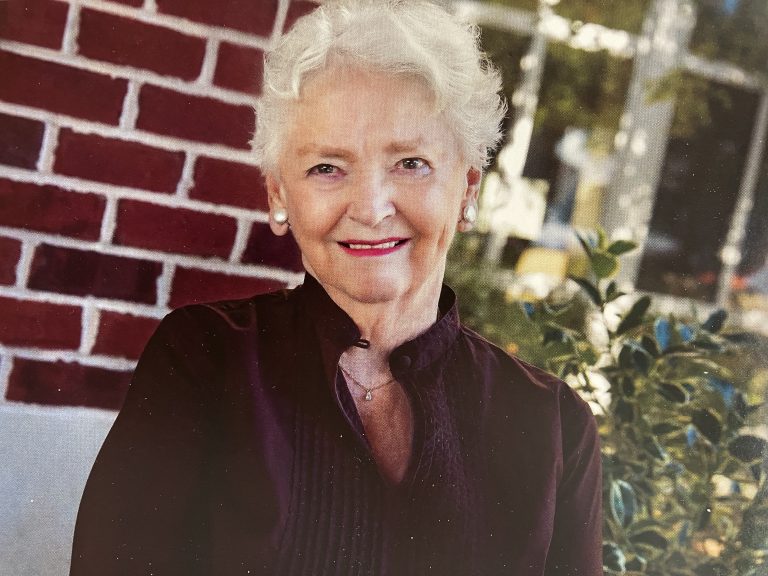

“Undergraduate education, in my mind, isn’t only about career preparation, but also about self-cultivation and preparation for democratic citizenship,” said Amy Ansell, dean of liberal arts at Emerson. “I [also] believe it really enriches career preparation. If you’re a film student, liberal arts is going to offer a breadth and a depth of perspective that could only enrich the ideas and the content of the stories that you’re telling. It’s both an addition to and an enrichment of the focus of the major at Emerson.”

“Undergraduate education, in my mind, isn’t only about career preparation, but also about self-cultivation and preparation for democratic citizenship.”

Amy Ansell, dean of liberal arts, Marlboro Institute

A sampling of recent self-designed majors underscores how the liberal arts brings together diverse disciplines and perspectives, enabling students to interrogate, understand, and even change the world around them: Arts and Activism, Creative Writing and Disability Studies, Social Advocacy and Postcolonial Studies, Art and Politics, Marginalized Contemporary Art, Writing for Social Change, and Writing and Publishing on Inequality.

“I think what matters about the liberal arts is how it encourages interdisciplinary approaches to scholarship,” Pyne said. “You’re able to understand how the subject connects to and relates to the world around it.”

A Unique Alliance

Pyne created his major last year, with the help of his advisor, as part of the Individually Designed Interdisciplinary Program (IDIP) in Emerson’s Institute for Liberal Arts and Interdisciplinary Studies.

Liberal arts and interdisciplinary studies have long played a role at the College. This past summer, that role was strengthened even further when Emerson and Marlboro College, a small liberal arts college in Vermont, finalized an alliance that strengthened Emerson’s liberal arts and interdisciplinary studies program, establishing a newly named entity: Marlboro Institute for Liberal Arts and Interdisciplinary Studies at Emerson College.

“It really is a change, in that the Marlboro Alliance opens a new pathway for students to enter Emerson as a major in the liberal arts, pursuing an interdisciplinary studies degree,” Ansell said.

In addition to the 14 first-year students who have entered this fall as liberal arts majors, there are 53 former Marlboro sophomores, juniors, and seniors who have come to Emerson to complete their interdisciplinary studies degree. Eighteen tenured and tenure-track faculty have come to Emerson from Marlboro as well.

Honoring Marlboro’s Legacy

Over the last decade, more and more small colleges and universities across the United States found themselves in the unfortunate position of having to close their doors, due to a number of factors, including declining enrollments, increased demands on financial aid, and annual operating budget deficits. But colleges that are open to change and growth can help preserve their legacy and continue to play vital educational roles into the future—such as Marlboro.

Emerson President Lee Pelton has stressed the importance of creativity, collaboration, critical thinking, and communication as key elements of the liberal arts and qualities that both Emerson and Marlboro cultivate. In a letter last year to Marlboro president Kevin Quigley, Pelton wrote that these characteristics are “what we need to solve the serious problems that our society is facing, and to bring into being—in Shakespeare’s phrase—the ‘brave new world’ of the future.”

Pelton’s statements are a powerful antidote to the mantra of critics of the liberal arts and humanities who say the subjects do little to prepare students for life in the real world. In this most tumultuous year, it seems the value of the liberal arts has never been more pertinent. A July article from Inside Higher Ed made the argument that “this moment, perhaps like no other, has revealed the value of a well-rounded liberal arts education.”

Asking Important Questions

One needs only to look at the Marlboro Institute’s course listings to find a class that is culturally relevant: There are courses that examine subjects such as social change, environmental economics, feminism, power and privilege, post-racial America, and queer identity.

“I think asking questions as a response to the world is a key part of a liberal arts education,” said Adam Franklin-Lyons, an associate professor in the Marlboro Institute who specializes in medieval history and who is one of the faculty members to join Emerson from Marlboro. 2020 could not possibly be a better time for young people to ask these important questions and try to find solutions.

Many courses and areas of study in the liberal arts have a strong emphasis on civic engagement, which is one of the College’s core values. The Emerson Prison Initiative (EPI) is one such example. Headed by Marlboro Institute Associate Professor Mneesha Gellman, EPI provides a high-quality liberal arts education to people incarcerated at Massachusetts Correctional Institution at Concord. In 2017, Emerson College became the 12th member of the Consortium for the Liberal Arts in Prison.

“I think asking questions as a response to the world is a key part of a liberal arts education.”

Adam Franklin-Lyons, associate professor, Marlboro Institute

Additionally, many of Emerson’s accomplished faculty conduct extensive research in their fields and draw on this work when teaching. Marlboro Institute Professor Wyatt Oswald, an environmental scientist, has conducted a revolutionary study about how climate impacted the ancient New England landscape. Faculty members who joined Emerson from Marlboro have also added their expertise in: biology, chemistry, religion, physics, astronomy, mathematics, and political science, to name a few.

And, of course, one of the hallmark elements of the IDIP program is that students can design their own major, like Pyne, and pursue their own unique projects. “What’s really distinctive about the interdisciplinary studies program is that it’s based on student-led inquiry and interdisciplinary investigation around a theme or set of questions. Students are supported in that self-designed course of study from the first year through the senior year with Marlboro seminars specifically designed for those students and to support them through that process,” Ansell said.

Looking Toward the Future

Cross-departmental collaboration is one of the many aspects that makes the liberal arts at Emerson stand out. Additionally, professors in any department may join the Liberal Arts Council, a faculty committee that provides input on the curriculum and programming of the liberal arts at Emerson.

In 2016, Eiki Satake, professor of mathematics and statistics in the Institute, and David Maxwell, professor emeritus in the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders (CSD), collaborated on a project with the goal of changing the way research methods were taught in classrooms by introducing students to Bayesian statistics instead of traditional statistical methods.

Jon Honea, an associate professor in the Marlboro Institute who studies Massachusetts dams and rivers, has co-taught a course on the environmental economics of rivers with Nejem Raheem, an environmental economist in the Marketing Communication Department.

One particularly memorable student project that transcended departments, according to Amy Ansell, was Cow Power, a 2013 documentary created by Allison Gillette ’12, which explores the possibility of cow manure as a leading source of renewable energy on farms. The film was shown as part of the Department of Visual and Media Arts’ Bright Lights film series in 2013.

“I think what’s so intriguing and special and unique about Emerson is it is so strongly focused on the professional fields, but then builds in liberal arts to strengthen the education as liberal arts connects to each of those professional areas,” said Ansell. “So in that way, it’s really the inverse of liberal arts colleges that are trying to find a foothold with relevance for professional endeavors. We already have that, but we are strengthening liberal arts through the lens of those fields.”