Opportunities for Understanding

Every day, Americans are reminded of how polarized we are—on our social media feeds, in our conversations with co-workers, at our dinner tables.

The US has long been divided over the major issues of our day. But those divisions have been on the rise. A recent study published in The Review of Economics and Statistics reported that political polarization in America

has been increasing for the last 40 years, at rates higher than any other industrialized nation among the 12 studied. The consequences of this state of affairs can include “reducing the efficacy of government…increasing the homophily of social groups…and altering economic decisions,” according to “Cross-Country Trends in Affective Polarization,” published in the March 2024 issue of the peer-reviewed academic journal.

Polarization is evident everywhere we look: in Congress, in the media, on college campuses, at the dinner table. How did we get here, and how can we learn to actually talk to, not shout at, one another again?

No Winners or Losers

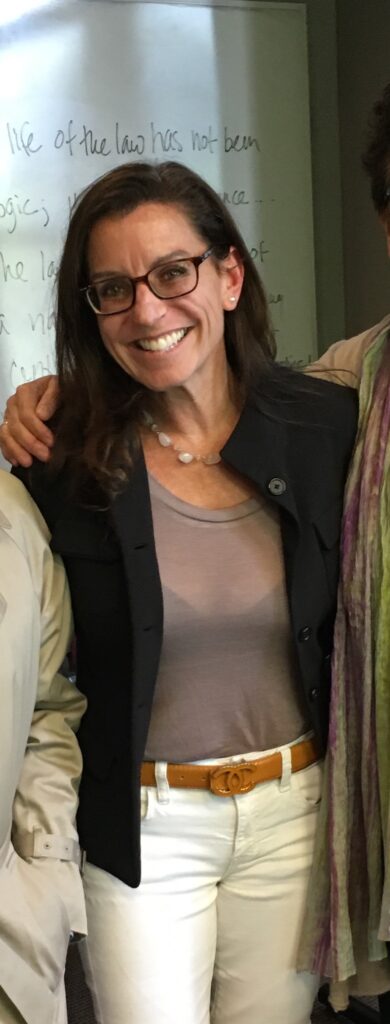

Israela Brill-Cass facilitates tricky conversations for a living. A senior affiliated faculty member in Emerson’s Communication Studies Department, Brill-Cass works as an independent ombuds, attorney, mediator, and facilitator.

One of the pitfalls of talking with someone with whom you have strong disagreements, Brill-Cass said, is framing the conversation as zero-sum: one of you will win, and the other will be “vanquished” by truth or logic.

“The framing that I give to students, the framing that I give to folks who come and talk with me as an ombuds, is that conflict is an opportunity to create understanding,” she said.

People approach dialogue with unique lenses and personal realities that can include power dynamics, intersectionality, culture, neurodiversity, and identity, Brill-Cass said, all of which underlie and transcend the actual topic of conversation.

“There are so many differences operating under the surface. We know what we intend to say to someone, [but] the impact could be completely different, and it’s the impact that matters,” she said.

It’s also important to realize that Americans have been exposed to intense polarization for nearly a decade, and that affects how we approach people with different views, said Brill-Cass.

“Everything feels like it’s at an 11…we need to slow down the cortisol…and just recognize that everybody is sort of at that level of real tension,” she said.

In practical terms, Brill-Cass said she approaches each mediation by setting the bar low. It’s not about everyone walking away with a resolution or one party winning; it’s about increasing understanding and dialing down hostility.

“The idea, I think, is that there’s mutuality. You’ve had this conversation, you’ve exposed some things that you might not have felt comfortable doing otherwise…at a minimum, what they come away with is an opportunity to actually have been heard—maybe not agreed with, but heard—by somebody who they’re in conflict with, and that can be transformational,” she said.

Progress, Not Shame

Tina Smith ’74 is also focused on helping people work together—or work together better—despite their different backgrounds.

In 2017, she founded D&I Strategists, a Washington, DC–based consultancy that helps organizations assess their culture; address division; and thrive through diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB). The business had been growing slowly but steadily until May 2020, when George Floyd was murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis.

“After that, we exploded, because everyone was asking for support,” Smith said.

Oftentimes, DEIB work can provoke uncomfortable discussions and unexpected feelings, Smith said. In order for it to be successful, Smith says she takes the time at the beginning of the process to have tough conversations “without blame, shame, or guilt.”

“People get tired of hearing me say this, but I love the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King’s statement. He said, ‘We may have all come on different ships, but we’re in the same boat now,’” Smith said. “I don’t care whether your [great-great-]grandparents owned slaves or not…what I want to know is, what are we going to do now? How do we address this issue so that your grandchildren aren’t still dealing with this?”

Smith, who studied Communication Disorders at Emerson, said the ability to listen carefully and a willingness to take risks—skills she learned at the College—have proven to be critical in her current work.

She’s also learned to ask the right questions, including who in the organization will “own” the work. Because in order for a culture to change, everyone needs to be on board and incorporate the skills and lessons.

“The diversity program is not a separate entity—like accounting and human resources, it should be embedded,” she said. “It’s not what you do, it’s how you do it.”

What’s So Funny?

When the person with whom you can’t agree is a friend or family member, sometimes all you can do is laugh.

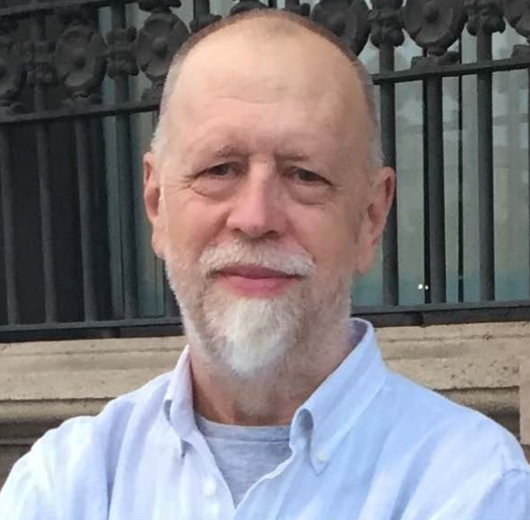

Communication Studies Professor Phil Glenn is the author of Laughter in Interaction (Cambridge University Press, 2003) and co-editor of Studies of Laughter in Interaction (Bloomsbury, 2013), among other published

articles and chapters. He said a lot of times, conflicts can seem enormous because our identity feels threatened, or they cause us to experience anxiety or anger.

“But sometimes, those can be moments where a bit of lightness of being, a bit of laughter, can help remind us that this is not the end of the world; this is just a moment and we can move past it,” Glenn said. “And that’s especially true in ongoing close relationships where really, the relationship is more important most of the time than any one single issue.”

But what about when you’re sparring with someone you barely know—or never met in your life? Humor and playfulness don’t often work to diffuse online conflict, Glenn said, because you and your interlocutor don’t have a baseline of trust, and nonverbal signals—critical to understanding humor and play—are absent (emojis notwithstanding).

And there’s something else that’s frequently missing from discourse in our polarized world: a shared sense of reality.

These “reality disjunctures,” Glenn said, using a phrase coined by the scholar Melvin Pollner, are tough to overcome and are reinforced by “echo chambers” of news sources, social media, and our own very human impulses to seek out like-minded people with whom we have an easy rapport. We need, as a nation, to try to find agreement on some basic facts, which isn’t glamorous and won’t be reported in the news, he said.

“Conflict is much more exciting and interesting, but…we need to come to some greater sense of what are some core commitments and core senses of what’s real,” Glenn said, “and then we have to try to slow down the temptation to demonize those who see the world so differently.”

Lessons From Abroad

One way to help people with different worldviews coexist peacefully is by bringing them together around some common goal or desire, according to Jennan Al-Hamdouni ’09.

For the past decade, she has worked with nongovernmental organizations across North and Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and Afghanistan, most recently as a humanitarian access training manager based in Kabul, where she trained Afghan and international aid workers to negotiate with the Taliban in order to gain humanitarian access for aid organizations.

As a graduate student in conflict resolution and coexistence at Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Al-Hamdouni studied restorative justice and confidence-building measures in places that have experienced conflict.

Confidence-building measures work to restore trust and rebuild relationships between individuals or communities while, or after, harm or injustice has taken place.

“It allows those harmed and those responsible to engage in dialogue that can result in acknowledging responsibility, acknowledging wrongdoings, and finding ways to make amends. The goal of this approach is to restore relationships, deprioritize punishment, and humanize all parties in order to prevent conflict from returning,” she said.

One example of confidence-building in action that Al-Hamdouni was previously committed to centered on the disputed territory of Western Sahara. Morocco claims the territory and wants to hold onto it, in part, because of its phosphate-rich off-shore resources. Algeria supports Western Sahara as an independent state, which would provide Algeria access to the Atlantic Ocean. The country also allows Sahrawi refugees to live in camps on Algerian soil, adding to tensions between the two nations, according to Al-Hamdouni.

UN aid workers brought people living in the Western Sahara to the island of Madeira, along with Moroccans and refugees who fled to Algeria. There, participants were able to see family members they hadn’t seen in decades and engage in dialogue with ordinary people from the other side, she said.

“Essentially, everybody is able to spend time together and understand each other, while also being able to unite with family. So, there is some spice sprinkled into all of that so that people are appeased, they feel like they’re listened to, and they all go home…with a little less of a bitter taste in their mouths,” she said.

There have been successful examples of confidence-building in the US around very specific types of conflict, such as gang violence, Al-Hamdouni said. But in the case of our national polarization, she feels like the country is a long way from “getting in the room together.”

“I don’t think we identify as one thing anymore, and one of the integral parts of confidence-building measures is that there is a commonality,” she said. People from different parts of the country get information from different sources, listen to different politicians, and support different policies. “We are not even in the same book, let alone on the same let alone on the same page. We’re in different libraries altogether.”

Closer to Home

At Emerson, College leadership is banking on the fact that, when it comes to values and vision, there is more than enough commonality to foster constructive conversations and strengthen a sense of community.

This fall, the College launched EmersonTogether, an initiative that aims to break down the silos that can form within an institution; build skills for living within a pluralistic community; and create common experiences in the form of events, performances, and conversations. Given how colleges often act as microcosms of larger sociopolitical issues, the timing of EmersonTogether was crucial.

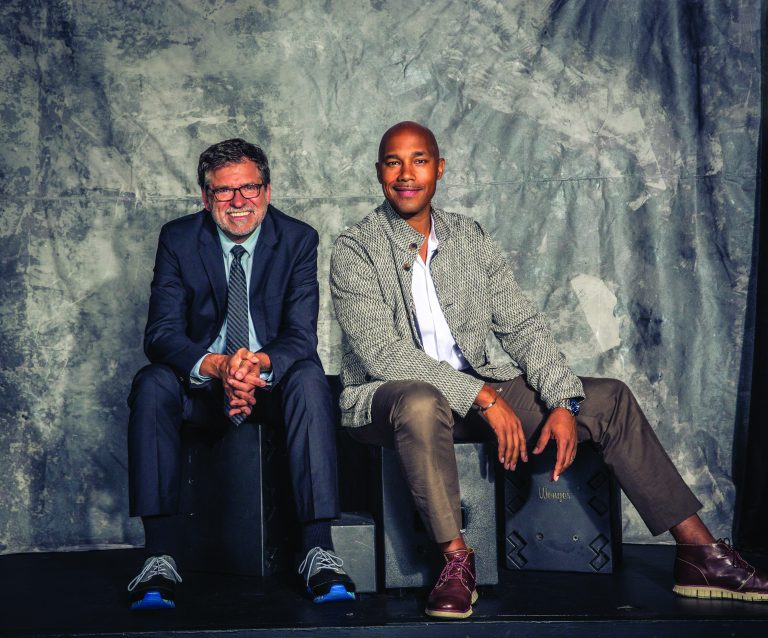

Shaya Gregory Poku, Emerson’s vice president for equity and social justice, and one of the architects of EmersonTogether, said the team felt it was important that the initiative speak to what members of the community are hungry for, and that the programming and capacity-building isn’t top-down, but the result of listening to what those needs are.

Countering polarization and building community takes persistence and empathy, Gregory Poku said, and a different mode of engagement that prioritizes understanding over conversion. It also requires that everybody feels safe to engage and that there are opportunities for people to “come to know each other as humans,” she said.

“Because at the end of the day, if you get to know a person, you can disagree with them politically, because you’ll have other contexts and points of understanding about who they are outside of their political beliefs.”